RED KITE (Milvus milvus) - Milan royal

© Arlette Berlie

Summary

Both a resident and summer visitor to Switzerland, reaching high densities in Central regions. Frequents farmland and small villages. Numbers have increased dramatically in the past 20 years. The call is a very human-sounding long whistle followed by modulations:

Red Kites are present in Switzerland throughout the year, with fewer in winter than during the breeding season. Their annual migration tends to be North-east/ South-west and with Spain, especially, being important as their wintering quarters, and higher numbers can be seen as they pass over Switzerland. The entire global population of Red Kites occurs within Europe and small parts of North Africa. Spain, Germany, Sweden Poland and Switzerland hold 95% of the individuals.

© Arlette Berlie

The Red Kite is arguably the most beautiful bird of prey in Europe, living up to its French name “milan royal”. It has almost translucent pale “windows” in the lower surface of the wings, which contrast sharply with the long black tips of the primaries and dark carpal patches. It has a generally rufous body, and a tail which is pale below but red on top. Finish this off with an almost white head and you have a strikingly patterned bird. This colouration means it is easily distinguished from a Black Kite in good light; but in silhouette it is larger than the Black Kite, with a longer much more deeply forked tail, and a flight pattern that is more “bouncy” and loose winged than the Black Kite.

In silhouette the deeply forked tail and looser wings separate the Red Kite from the Black. © Arlette Berlie

The Red Kite is a conservation success story. Persecution had reduced the numbers dramatically from the mid-19th century onwards, but increasingly successful protection over recent decades has meant a population re-bound. In Switzerland the numbers have increased more than 3-fold in the past 20 years with about 3000 pairs now nesting. Reintroductions in the UK have also been hugely successful. It may also be one species that has benefitted from a warmer climate as the numbers over-wintering have risen to about 3000 individuals in Switzerland. These being mostly adults who may be avoiding the risks of migration.

Like the Black Kite it is both a scavenger and a predator, foraging opportunistically for both live and dead items. It favours agricultural areas, where there are fields separated by plots of woodland for nesting and roosting, where there is waste around farms, and where harvesting activities can disturb or kill potential prey. In central Switzerland they can reach high densities, with numbers exceeding 20 pairs per 100 square kilometres in places (Knaus et al 2018). They also will form communal roosts, especially in winter (Cramp etal cite gatherings of up to 100). I have never seen this but it must be quite a sight.

Red Kites seem to thrive best in the rolling mosaic of fields and farmland in central Switzerland © Chris Hails

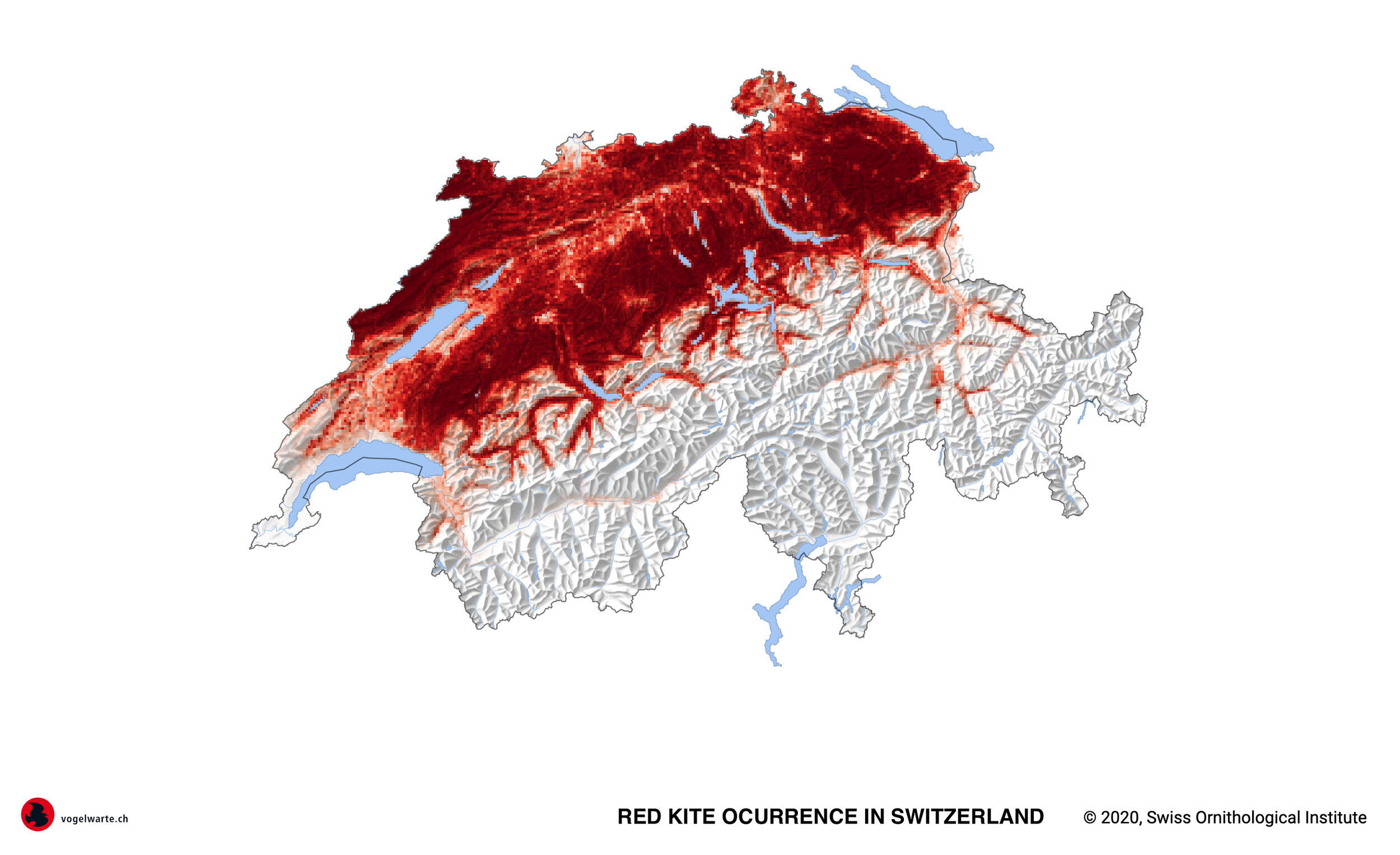

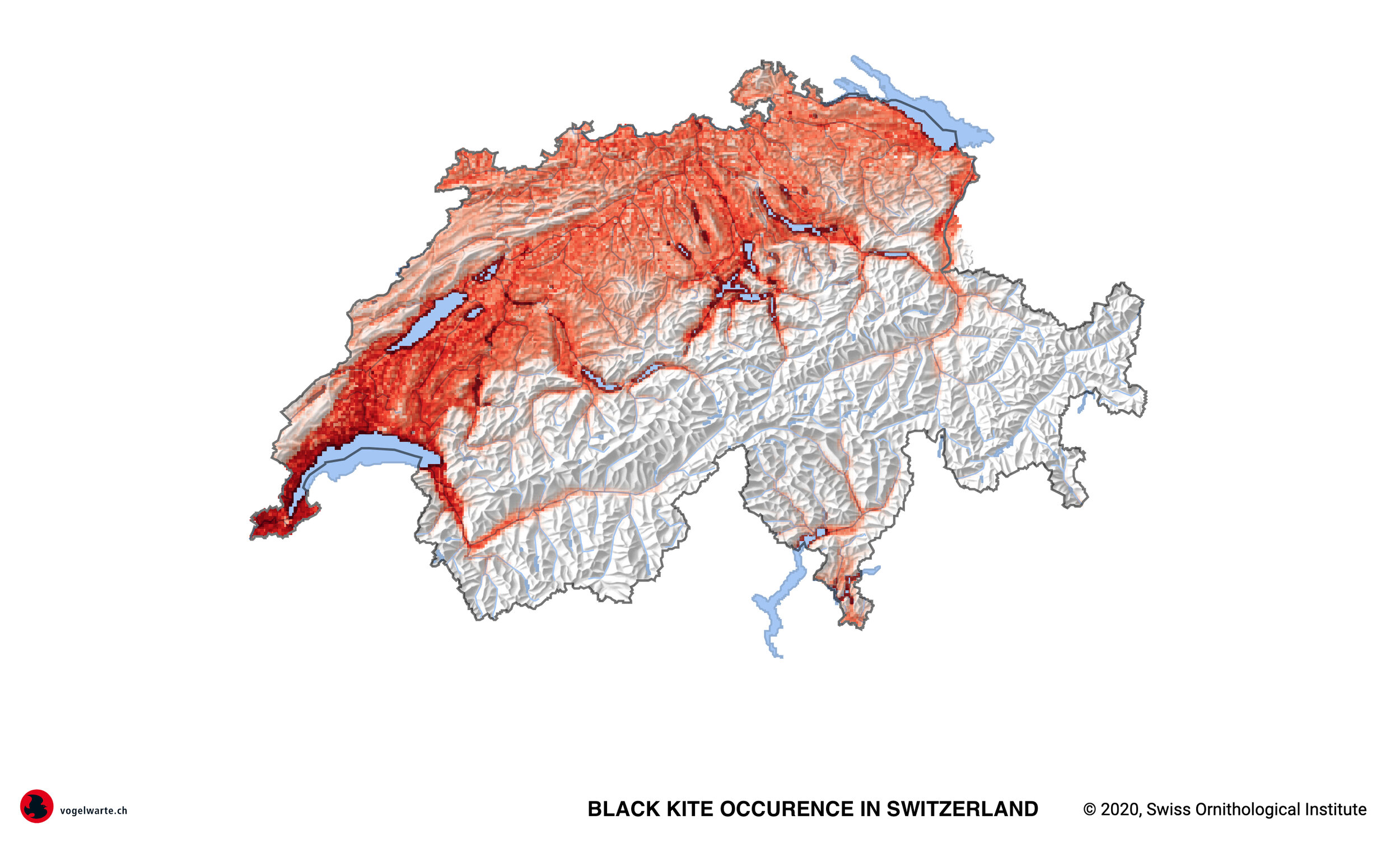

Both of the Kites avoid the high alpine regions and are found in the north of the country, but they sometimes penetrate into the low alpine valleys. The occurrence of Red Kites is much higher in Central and Eastern Switzerland than in the west, and that of the Black Kite is somewhat the reverse. Why this should be is not clear, but studies elsewhere have pointed to the fact that the Black Kite seems to prefer hunting over water bodies, and the Red Kite over open country (Zawadzka 1999). The presence of two large lakes, Lac de Neuchatel and Lac Léman, in the west may account for their somewhat complementary distribution, but it doesn’t seem to hold for the shores of Lake Konstanz in the north-east (see maps below of Red Kite (left) and Black Kite (right) from Knaus et al 2018).

The call of the Red Kite is structurally similar to the Black Kite in that it starts with a whistle which is then followed by some degree of modulation. However, there the similarity ends: the Red Kite’s whistle is lower pitched, starting at about 2.5kHz, rising sharply to about 3.0 kHz then descending to 2 kHz it is then followed by a variable number of slow modulations between 2 and 3 kHz, the sequence sounding like “whee-ee, wee-oo wee-oo”. The Black Kite whistle rises very sharply from 2.5kHz to about 3.5 kHz, and is more or less held steady at that frequency transitioning into very fast modulations around 3 kHz. Here are sonograms of both, Red Kite first, repeated twice:

Four calls in the following order: Red Kite; Black Kite; Red Kite; Black Kite.

As you can hear, the Red Kite call has a strange human quality to the tone, especially as it swings up and down during the modulation second phase - almost like a farmer whistling to his cows!! Solitary birds call only at intervals, so here is an extract of five calls from a perched bird which was calling about once per minute. I edited the gaps between calls:

The red upper side of the tail is often only visible when the bird turns. © Arlette Berlie

Plenty of farm and village noises in the background there. That particular bird finished each call with just two modulations, and seemed pretty consistent throughout the morning I listened to it. However, in observing other birds, I found that the modulation phase can contain a variable number of modulations up to about 6 or 7. Here are several birds circling a field, calling to each other with anything between 2 and 7 modulated whistles. The first call even has two opening whistles before the modulations, so things seem to be pretty variable:

Whether those variations are attributable to different individuals or their state of excitement I cannot say. (That last piece had the lower frequencies heavily filtered to remove noise from nearby farm machinery and a road, but the call frequencies are unaltered).

In another location I found adults with two juveniles on the wing. The juveniles were calling with a rising mewing “wee-ee” call, reminiscent of gulls or maybe divers (loons):

The family flew off and joined other birds a few fields away so I followed to get more sounds. Again this was near a road, and had a pig farm close by so if you think you can hear pigs squealing, then you certainly can! It is quite a noisy scene with both excited adults and juveniles calling, but I thought it worthwhile including here as it is not often you get birds of prey quite so vocal:

Most of the basic adult mewing call seems to be about keeping contact and maintaining the pair bond (see also Cramp etal). They sometimes call in an almost synchronised manner described as akin to duetting (Cramp etal), although I am tempted to think it coincidental rather than planned. Listen to this example and see what you think:

…and yes that was a pig squeal at the end there!

© Arlette Berlie

So there you have the Red Kite in Switzerland - a beautiful bird with, to my ears, a pleasant and amazingly human sounding call, very different from other birds of prey in Europe.