Deliciously and subversively cryptic, Edward St John Gorey’s books, plays, postcards, toys, stage sets and costumes – indeed an entire lifetime of utterly sublime, mockingly apprehensive artistry and authorship – are celebrated and critically acclaimed by everyone from cultural pundits to goth cultists. The rare front-page New York Times obituary, on 17 April 2000, is testament to Gorey’s eclectic narrative range. “In creating a large body of small work, he made an indelible imprint on noir fiction and on the psyche of his admirers,” Mel Gussow wrote.

Yet, understandably, less attention is devoted today to the 200-plus illustrated paperback covers and hardcover jackets that Chicago-born, Harvard-educated Gorey (known to his friends as Ted) created while working as a staff artist, art director, editor and freelance illustrator at various American publishing houses for a large portion of his career. In two brief sentences, his obituary tossed aside this impressive output: “After graduation he remained in Boston, illustrating book jackets. Then he went to New York and worked in the art department at Doubleday, staying late in the office to create his own books.”

Still, these pen-and-ink crosshatched and hand-lettered gems from the beginning of his 50-year career arguably challenged prevailing American publishing conventions while they helped define Anchor’s and other publishers’ visual identities. His covers also released a troupe of melancholy Victorians and Edwardians, woeful infants and little tykes, and eerie reptilian and mammalian beasts that haunted his proto-graphic novel “novels”, which earned legions of loyal fans over the ensuing decades.

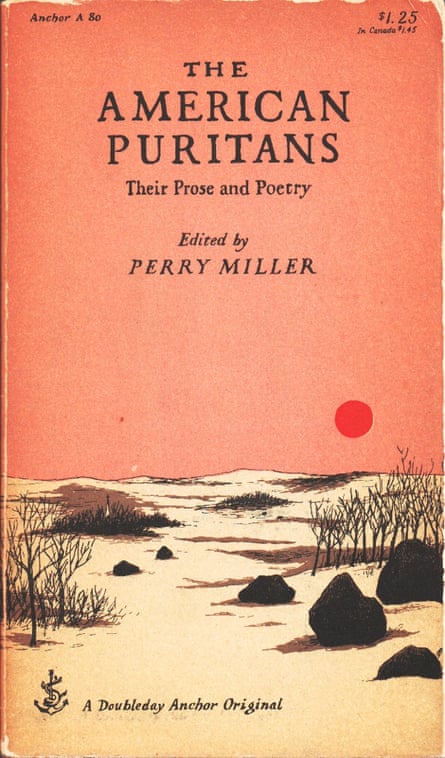

Commercial book cover design is a minor portion of Gorey’s award-winning legacy, but not a lesser art. His linear expression and droll comedy are integral ingredients. There are also covers that are stunning for their hidden allusions. The barren landscape, for example, on the cover of The American Puritans evokes an otherworldly quietude, but speaks to concealed psychological demons as well. Although these works are perceived as less significant because Gorey was responding to assignments from editors to illustrate other artists’ creative offerings, at the very least they serve as historical markers of Gorey’s evolving artistic persona. Yet some covers, such as the one for Alain-Fournier’s The Wanderer, have artistic integrity both on and beyond the specific volume.

A self-described inveterate reader of prose and poetry (an understatement, since at his death he possessed a personal library of 25,000 volumes), he effortlessly mastered the interpretive challenges endemic to book-cover art, while injecting tics and quirks for his own amusement. Gorey’s covers and jackets were not done anonymously or as mere throwaways, as many others were. Nor was this a strategic compromise until he found and embraced his true calling. Today, this body of work exemplifies his unique contribution to a truly exceptional era of graphic design when book covers and jackets became an innovative genre honoured by exhibitions and awards.

Gorey’s English neogothic credentials were unassailable. As far as draftsmanship goes, he was inspired by early 20th-century English artist, illustrator and author Edward Ardizzone, whose own 19th-century-inspired, crosshatched, linear and watercolour styles, though somewhat looser than Gorey’s, graced the covers and interiors of many early- to mid-20th-century books and were mainstays in Gorey’s personal library. “I had a penchant for the British and was aware of British book jackets because I bought a lot of British books at the time,” he said. English contemporaries of Ardizzone, including linear maestros Edward Bawden, Rex Whistler, John Piper and Paul Nash, whose work captured the hell of trench warfare during the first world war, probably gave Gorey more to either reference or parody. He did not directly mimic but rather incorporated certain attributes. Gorey’s work was not pastiche but reflected his passion for the trappings of a particularly romanticised yet cautiously melancholy epoch. It was not a priori lugubrious – but, rather, joyfully dark.

A few years before his death, Gorey suggested to me in an interview that his covers and jackets were as much a part of his creative grand plan – the building of an interconnected oeuvre –as any of his more authorial work. Demonstrating his indefatigable willingness, he added: “I still do book-jacket work occasionally, if somebody calls me up.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion