Plastic Has Changed Sea Turtles Forever

Even if plastic pollution stopped tomorrow, turtles would be dealing with the repercussions for centuries—at least.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on hark

As recently as the 1960s, perhaps later—within the life span of Tom Hanks, and within a few years of when the world was using its very first ATMs and contraceptive pills—nearly all of the planet’s sea turtles were living plastic-free lives. They hatched on plastic-free beaches, digging their way to the surface through plastic-free sand; they waddled into plastic-free waters and munched on plastic-free algae and jellyfish. They ate and lived and died in a plastic-free circle of life.

Many of those sea turtles—a group of animals whose life span can reach 100 years—are still alive today. But they no longer live in the world they were born into. Plastics are now ubiquitous, not just in oceans and on shores but also inside the animals that make those habitats their home. Studies of loggerhead hatchlings off the coast of Florida have found that more than 90 percent of the teeny turtles, just a couple of inches in length, have swallowed plastic. By the time they reach adulthood, the numbers are even worse. “I’ve been post-morteming sea turtles since the ’90s and every single one has had plastic in its gut,” Brendan Godley, a conservation scientist at the University of Exeter, told me.

In just a few short decades, humans and our plastics have reshaped the world that animals inhabit. And reversing it could take ages, beyond the likely expiration date of many modern species. Even if all plastic pollution into the ocean halted tomorrow, “I think it would be at least a quarter of a millennium” before a sea turtle could even hope to be born into a plastic-free life, David Duffy, a wildlife-disease genomicist at the University of Florida, told me. And that’s an absolute-bare-minimum estimate. In reality, turtles may never return to the plastic-free existence they commanded for tens of millions of years, before our inventions upended it.

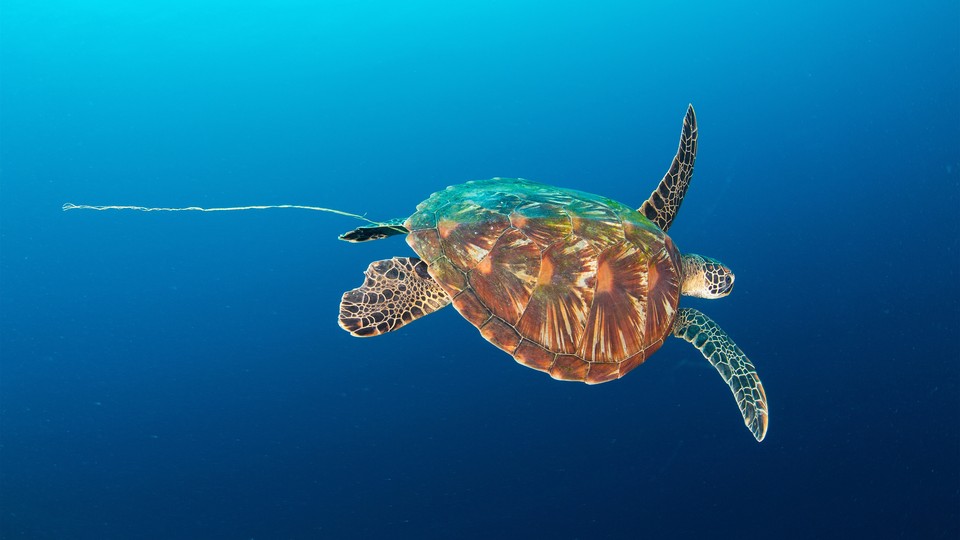

Sea turtles’ problems with plastic have always been manifold. Abandoned fishing lines and nets can lacerate their flippers or wrap around their neck; the entanglements can prevent the turtles from surfacing for oxygen and drown them. Plastic bags, which look an awful lot like jellyfish, can suffocate turtles or create fatal blockages in their guts.

Even after those items start to break down—a process that can take decades or centuries in the ocean—the microplastic pieces they leave behind continue to pose a threat. Hatchlings rummaging for seaweed often gulp down shards of bottles, canisters, and disposable packaging that can run more than 15 percent of their total body length; once swallowed, the jagged edges can perforate the turtles’ guts. Blunt bits of plastic can also build up in the animals’ digestive tract until it starts to dissuade the turtles from eating real food. In some cases, the masses of plastic inside the hatchlings can make up, as Duffy’s team has found, more than 1 percent of a turtle’s entire body weight. Even the subset of plastic that eventually gets passed can leave behind toxic chemical additives, or heavy metals that the polymers picked up in transit, that may linger in the turtles’ tissues.

Plastic can also suffocate the coral reefs that several species of sea turtles rely on for habitat, and remake the sandy beaches on which they nest. Female sea turtles have been documented inadvertently entombing their eggs beneath plastic debris. The accumulation of plastic on shores may even be worsening a problematic skew in certain turtle populations’ sex ratios. Like many other reptiles, sea-turtle sex is determined by temperature. As climate change makes sand hotter, many populations are turning unsustainably female; already, several beaches in Florida and Australia have clocked more than 90 percent of hatchlings emerging that way. As heat-retaining plastic continues to pollute beaches, the crisis is only likely to deepen.

Even if plastic pollution stopped tomorrow, turtles’ plastic problems would persist—though it’s difficult to say for how long. Plastics have been around for just a century; scientists don’t yet have a good grip on how long we can expect different types of them to last. All that’s for certain is that it will be longer than the history of plastics thus far. Polymers produced in the 1940s, when plastics entered mass production, are still with us today. Left adrift at sea, a plastic bag may no longer be visible to the naked eye after a few centuries, says Shreyas Patankar, an applied physicist at the conservation organization Ocean Wise. But the minuscule products of that breakdown are expected to stick around for much longer, potentially ferrying toxins all about. Brian Love, a materials scientist at the University of Michigan, gave me a very rough estimate for a particularly durable group called polyolefins, commonly found in bottles, ropes, even face masks: Several human lifetimes, even millennia, could pass before they fully disappear.

Sea turtles, too, have impressive longevity—but that very trait may work against them. Many don’t reach sexual maturity until their third or fourth decade of life; even with the magical appearance of plastic-free oceans, hatching a totally new generation into those safer waters would take a while. And there’s no guarantee that turtles hatched into an environment with no plastic in it would themselves be plastic free. Human placentas and rodent fetal tissues have been found to contain nanoplastics—contaminants they could have accumulated only by inheriting them from the mother. If something equivalent happens with sea-turtle eggs, as some evidence suggests could be the case, the plastic burden would be passed on and on, Heather Seaman, a biologist at Florida Atlantic University, told me.

All of that leaves turtles with a grim outlook. Diana Sousa Guedes, a conservation biologist at the University of Porto, told me that even if plastic pollution were to halt, it’s quite possible that there will never again be a sea-turtle generation that lives free of plastic’s grip. But the animals’ future could still look far better than it does right now. Every bit of plastic that humans remove from the oceans, and every piece that doesn’t end up there to begin with, is one fewer pollutant to clog the environment centuries or millennia from now, plaguing ocean wildlife, slashing up their bodies, knotting up in their guts.

No matter how long it sticks around, plastic is unlikely to be the great sea-turtle undoing: If anything, climate change, habitat destruction, or illegal harvesting is more likely to finish them off. Godley, though, doesn’t worry too much about the animals going extinct; some populations have actually been rebounding in recent years. Leatherbacks, for instance, “have been kicking around for 90 million years,” he told me. He thinks that our species—and our plastic production—has a higher chance of snuffing out first.