Tadelakt, an ancient lime plaster finish, is a three-millennia-old clean building solution that originated in Morocco. The all-natural material is antibacterial, hypoallergenic and regulates moisture — essential properties for a healthy living environment. Traditional lime plaster, which is free of toxic compounds, slowly reabsorbs carbon dioxide from the air and is 100% recyclable.

A rare artisan and ambassador of tadelakt

As part of our series on Clean Building Solutions for Slow Spaces, we spoke with Fabio Bardini, who has spent many years studying original texts about different traditional lime plaster techniques. He experimented with the original recipes to revive the lost art of true Venetian plaster and other traditional lime plaster finishes, including a technique called “tadelakt.” Now living and working in Salem, Massachusetts, the native Italian is one of only a handful of artisans in the United States who master the ancient tadelakt technique.

Tadelakt is based on an aged lime putty Bardini imports from his home country of Italy. “Anything built with lime, whether it is tadelakt or Venetian plaster or any kind of plaster made from the lime putty, is the ultimate green material,” he says. “When you use the lime putty, it will begin to carbonate and the material itself reabsorbs all the carbon dioxide released from the burning of the limestone, so it has a very low carbon footprint.”

Anything built with lime, whether it is tadelakt or Venetian plaster or any kind of plaster made from the lime putty, is the ultimate green material. – Fabio Bardini

In Italy, the lime putty has been produced the same way for thousands of years: Earth-abundant limestone is fired in wood-burning kilns at 900 degrees Celsius for several days before it gets slaked and aged in open-air pits for a minimum of three years.

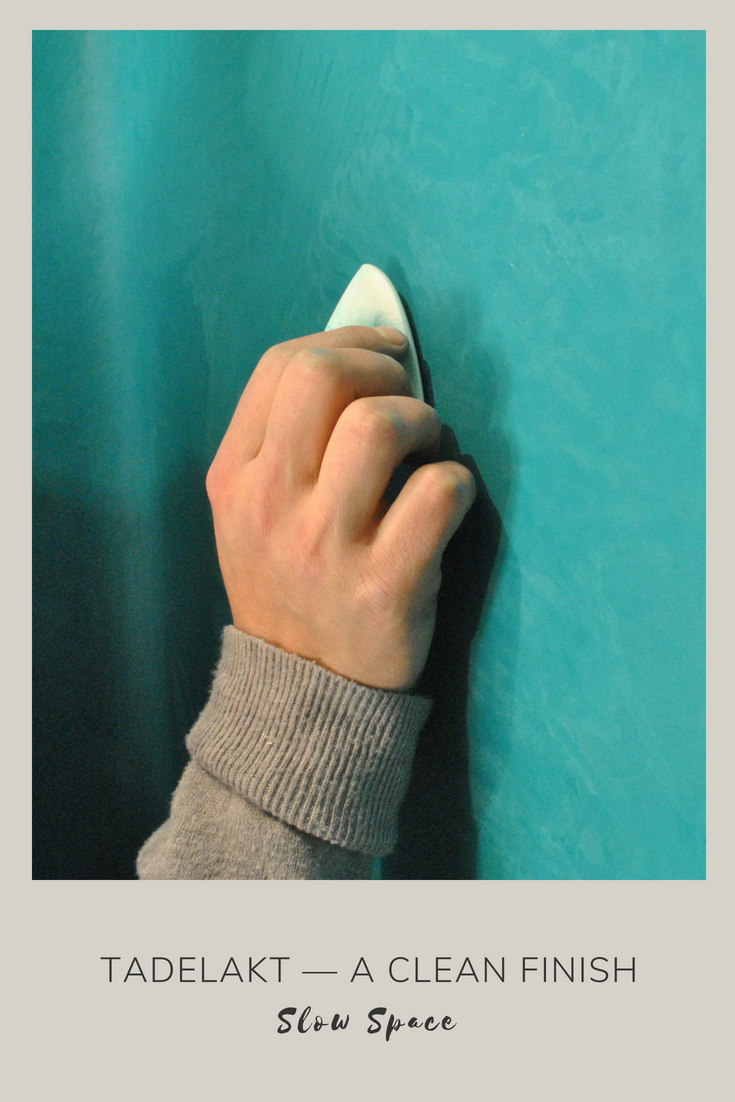

A time-consuming, intricate process that requires the skills of a “maalem” — a tadelakt artisan: The application of Marseille olive oil soap and polishing it with small semi-precious river stones gives tadelakt its silky feel.

Bardini makes his tadelakt primarily from the Italian lime putty, sand — silica sand or marble sand — and water. Other components, also all natural, can be mixed in. He applies the plaster with a small trowel (called a “cat’s tongue”). Once the lime plaster dries, it begins to absorb water again. That’s why an additional step becomes necessary to make the finish waterproof. “For the tadelakt, for example, we use Marseille olive oil soap, a traditional, ancient type of soap that is made in Marseille, France,” the skilled artisan says. “You rub it in with these hard, semi-precious stones, pebble-like, polished stones, and that gives the plaster that polished, smooth surface.” The chemical reaction between the olive oil soap and the carbonating lime — the so-called saponification — solidifies and waterproofs the plaster. Once cured, Bardini typically treats the plaster with natural beeswax to further protect the surface without altering its beneficial qualities. The velvety smooth tadelakt thus becomes an ideal finishing material for building sinks, tubs, floors, even entire shower rooms.

The origins of tadelakt

Tadelakt originated in Morocco, where the technique was used to line water cisterns for drinking water. “It’s a very good material to keep water because it’s antibacterial, antifungal and antimicrobial,” Bardini explains. The material is also high in pH, with a pH of 12.4. It has always been well known for creating a healthy environment, even in a home. For example, lime plaster finishes have long been used to paint basements and root cellars. “People would do that in the fall, before they would store all their winter vegetables, like potatoes and onions,” Bardini says. “It’s also been used to paint the cow stalls and other animal stalls before the animals give birth. So it’s an ancient sanitizer.”

Even before tadelakt was used in Morocco, it is believed that the Romans brought their lime plaster techniques to the North-African country on their conquest south. “The Romans were masters of these classic techniques using lime and aggregates like marble dust or marble sand,” Bardini says. “The Romans invented this finish called marmorino, which translates to ‘little marble.’ It was the lime putty mixed with the marble dust that they used to line the walls of their villas, and that resembled a slab of marble when you applied it. They brought that method along with them.” The Moroccans then adapted the lime plaster finishing technique to the implements and materials available to them. They used a different type of limestone, for instance. “And instead of metal tools, they used little rocks, little polished stones. So the finish has a style of its own, but the basic ingredients and applications are very similar to the Roman-style walls.” The beauty and benefits of tadelakt later brought the lime plaster finish to the hammams (public baths) and private homes in and around Marrakech.

Mixing Marrakech Lime with water and yellow pigment to make tadelakt in Morocco. Photo by Joaoleitao

Bardini first learned about traditional lime finishing techniques when he attended art school in Florence, Italy, and studied architectural history from the old Egyptians through the Renaissance period. “These types of finishes kept on resurfacing from Roman times through the 1400s. Then, with architects like Palladio, they again resurfaced around the 16th, 17th century,” he says. Much later, during the 20th century, the techniques experienced yet another resurgence, when architects such as the Italian maestro Carlo Scarpa brought the materials and applications into modernism. “These are beautiful finishes, sought after for their beauty and resilience,” says Bardini, who regrets that today very few craftspeople master these traditional lime finishing techniques in the United States. “They just get confused with modern, industrial products, but they look quite different,” he says. “Unfortunately, people give commercial plasters a lot of names: Stucco Romano or Venetian plaster per se, these are all products made with acrylics and a lot of chemicals. The classic materials of the past were very simple, made with lime putty and marble, and very little additions of these natural ingredients, like linseed oil or olive oil soap, and also beeswax for the final polishing. Those materials used for the past 3000 years never changed. You can still use all those materials and achieve the same results.”

“These are beautiful finishes, sought after for their beauty and resilience. – Fabio Bardini

An ancient art for patient people

With all the evident benefits and advantages of tadelakt, why then are these traditional lime plaster finishes — timelessly beautiful, long-lasting and environmentally friendly even by modern standards — not implemented more widely in the building field today? Besides blaming the lack of maalem (tadelakt artisans) who could train others in the United States, Bardini says about mastering the technique: “It’s more like trial and error, and people like me take the time to study and try and finally come to a good product that can be applied.”

Bardini considers himself both an artist and a craftsman. “And that’s the type of person you need to be to work with these finishes,” he admits. “It is very tedious.” Finishing a bathroom with tadelakt takes about two month, then a sink or a shower has to cure for a month before it can be used. Tadelakt continues to change its color and harden over the months, years and even decades. “So it’s important to be very careful when it’s first applied,” says Bardini. “It is softer in the beginning, so if you were to do a floor in tadelakt, you wouldn’t want to walk on it with shoes at first.” After this initial time period, though, tadelakt becomes very durable and will last for many years, according to the master.

Tadelakt is a popular finishing material for building sinks, tubs, floors and showers. Photo by SpOon.

What’s more, traditional lime plaster finishes are typically applied directly over masonry structures. “So we have an additional challenge here in the United States, being that buildings are stud-framed,” Bardini points out. To apply tadelakt over stud-framed construction and modern substrates such as drywall prior preparation of the surface is necessary. Tadelakt in wet environments requires a cement board and a half-inch-thick lime-and-sand plaster base.

Bardini describes the tadelakt surface as being “hard as stone yet soft as silk,” and to appreciate the allure of tadelakt, he says it is necessary to caress it. “The beauty of these finishes is unmatched by anything available commercially or industrially produced,” he says. “But, you know, there are people who are willing to go through the process and to pay for the work, and they will enjoy it for the rest of their lives.”

The beauty of these finishes is unmatched by anything available commercially or industrially produced. – Fabio Bardini