In 1909, Marcel Leyat, an engineer from the tiny mountain town of Die in southeastern France, designed and built his first airplane. Not long after, he ran out of money. The young engineer had trained in aeronautics, only to find his skillset obsolete in a market controlled by the military; bespoke airplanes were a dying business. Undaunted, Leyat turned his attention to the pursuit of his real dream: building what he called a “plane without wings.”

Or, in other words, a propeller car.

Leyat was far from the only engineer developing an obsession with propeller power at the time, but he may have been the first one who came to the propeller cult directly from a career building airplanes. Leyat believed the aerodynamic design principles that made flight possible could at least make ground vehicles a bit more fuel efficient. Engineers were applying these principles across all kinds of vehicles in France at the time; some briefly anointed propellers as the propulsion method of the future for every imaginable mode of travel.

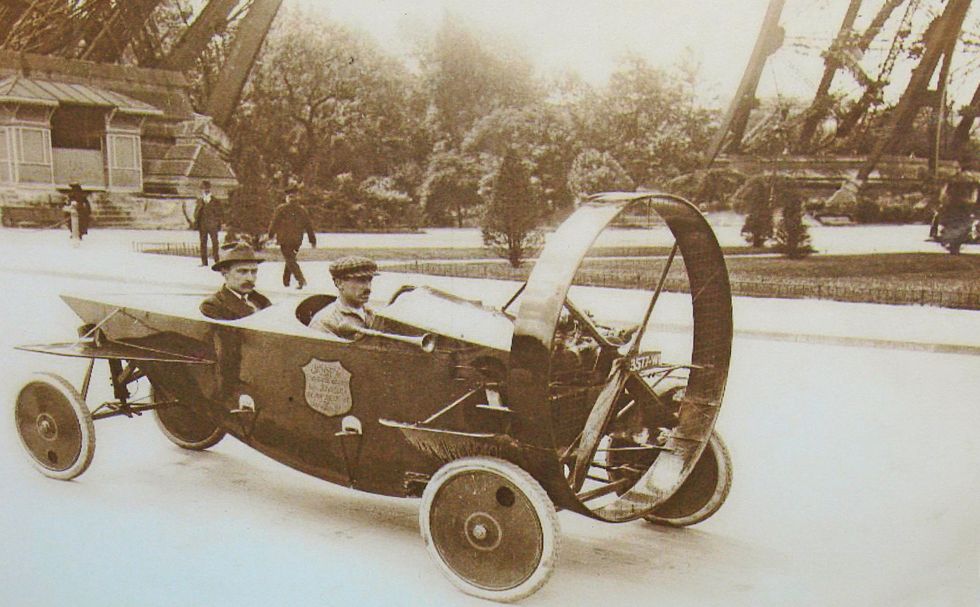

For five years, Leyat wrestled with propellers and repurposed airplane engines. For his aerocar straight out of steampunk fantasy, Leyat chose a name inspired by the ancient Greek word for spiral, as in helix and helicopter, which was undoubtedly less demonic-sounding to Parisians than to modern English speakers. Pamphlets advertised the “Hélica” or “Helicycle” as a stylish new vehicle designed by the science of the sky: it embodied speed, safety, and elegance, all in a sleek, aerodynamic chassis.

Leyat’s prototype applied the aerodynamic principles of flight design to the needs of an increasingly speed-crazed Parisian elite. The chassis was a smooth, enclosed chamber, shaped like a giant plywood teardrop, with two aluminum wheels supporting an enormous wooden propeller at the front and one more wheel at the back. Later models added stability and some much-needed seriousness to the Hélica’s profile. The wooden frame made it exceedingly light for a car at around 550 to 650 pounds, some 800 to 900 pounds lighter than its much more popular competitor, the Ford Model T.

In fact, everything airplane-like about the Hélica was a multiplier for danger at ground level. Aerodynamics, for example, enable the extreme speeds necessary to keep the vehicles aloft. But land travel favors more humane speeds, especially on the busy cobblestone squares of early 20th-century Paris.

Somehow, Leyat got his prototype—“one of the most preposterous vehicles known to man,” according to one historian—licensed to drive on public roads. Clips from a 1924 film show one of the later, four-wheeled Leyat models careening through a park and down narrow city passages and past onlookers frozen in terror.

The experience was hardly relaxing for the driver. The view of the road was perpetually obscured by the top half of the 5-meter-wide airplane propeller; the unprotected bottom half threatened to slice up any slow-moving pedestrians. Like an airplane, the Hélica featured cable-operated rear-wheel steering, which is ideal for high-speed turns in midair, but completely unmanageable on the ground.

The stress of driving a Hélica was magnified by the noise and inevitable wind tunnel effect of placing a driver right behind an airplane propeller. The prototype was an unsteerable murder machine, combining all the discomfort of airplane flight with the collision risk and threat to civilian life of modern mass-market automobiles.

This was the car that debuted at the 1921 Paris Auto Show, after which Leyat himself reported receiving over 600 inquiries from potential buyers. Production was exceedingly slow, however; each model was hand-built to order at Leyat’s factory on the Quai de Grenelle in Paris. By the time the first dozen orders had been filled, the propeller fad was over. Leyat built a total of 30 propeller cars in his lifetime and sold 23.

But it wasn’t all failure. As planned, the Hélica was ludicrously fast. A four-wheeled model with a mercifully enclosed cabin achieved a speed of 106 miles per hour in a record-setting race at the Montlhéry track in 1927, two years after the car was finally decommissioned. Leyat had also been correct in his prediction that the simplified hardware, which had no transmission, rear axle, or clutch, would make the Hélica more fuel-efficient, according to historians at the Lane Motor Museum, where one of the four remaining original models is still on display.

Descendants of the Hélica’s propeller-car legacy have cropped up in the luxury car world occasionally in the last century. Maybach even built a luxury sedan with an airplane engine in 1938. Outside of collectors and tinkerers, though, the most important source of demand for prop-driven vehicles has been the military. Multiple generations of Russian war tanks in both World Wars would have qualified as propeller-powered “aerocars” by Leyat’s standards; armored propeller vehicles were even mounted on skis to help defend against the Germans in the Second World War.

Claude Guéniffey, a vintage car connoisseur and president of the Hélica Fanclub, maintains the car was a milestone in vehicular engineering.

“It’s the only propeller car to have been produced in series—a short series, but a series nonetheless,” Guéniffey says. (Most other attempts at aerocars ended with a prototype.) And if the experience of driving one is nightmarish, it must be considered in relation to that of other early attempts at motorcar design.

“I’ve driven a Hélica,” says Guéniffey, who travels the world to speak to automotive history fans and visits vintage car expos in his free time. “It wasn’t too difficult for a car of that time.”

Lynne Peskoe-Yang is a science writer and researcher in New York. Her reporting on civil engineering, machine learning, and artificial intelligence has appeared in Marketplace, IEEE Spectrum, Rewire.org, and Sludge; her essays on science and language live over at Popula.