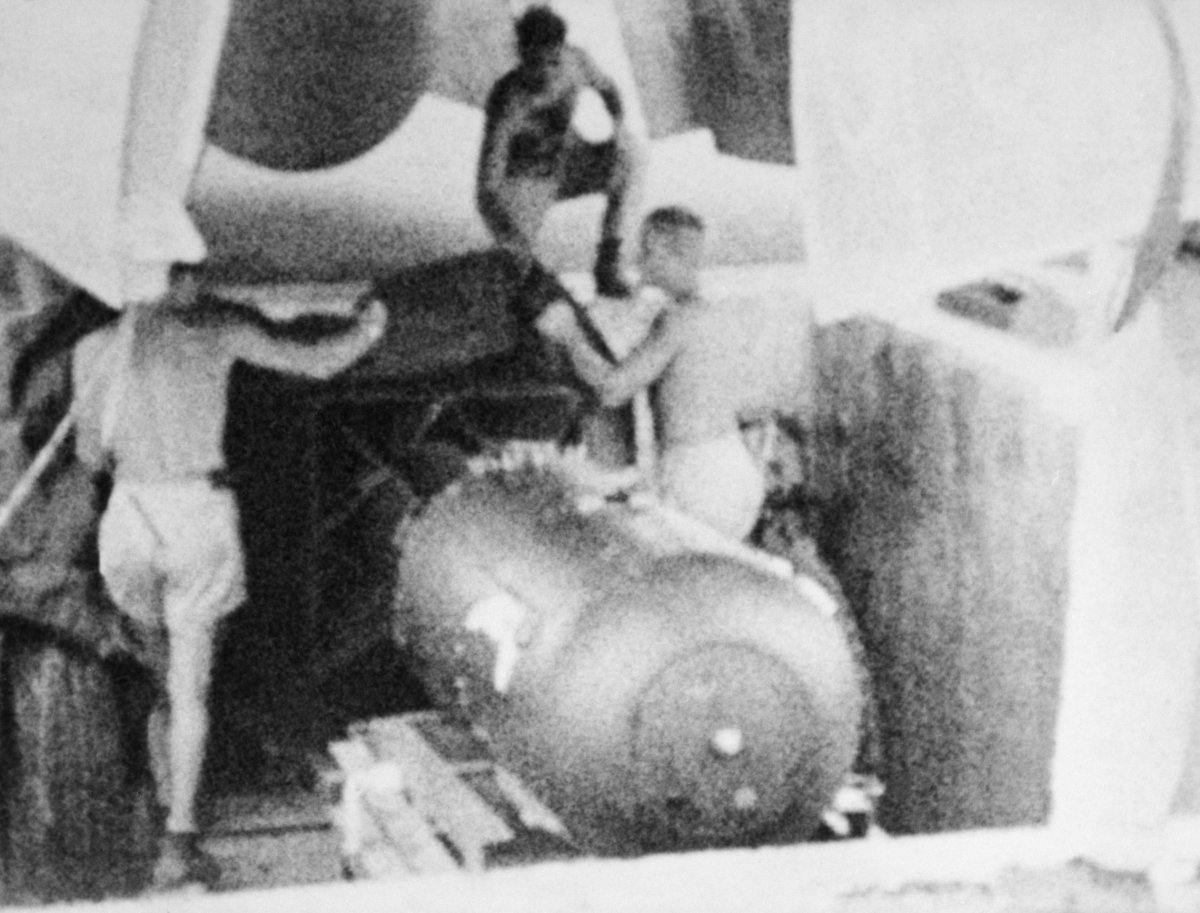

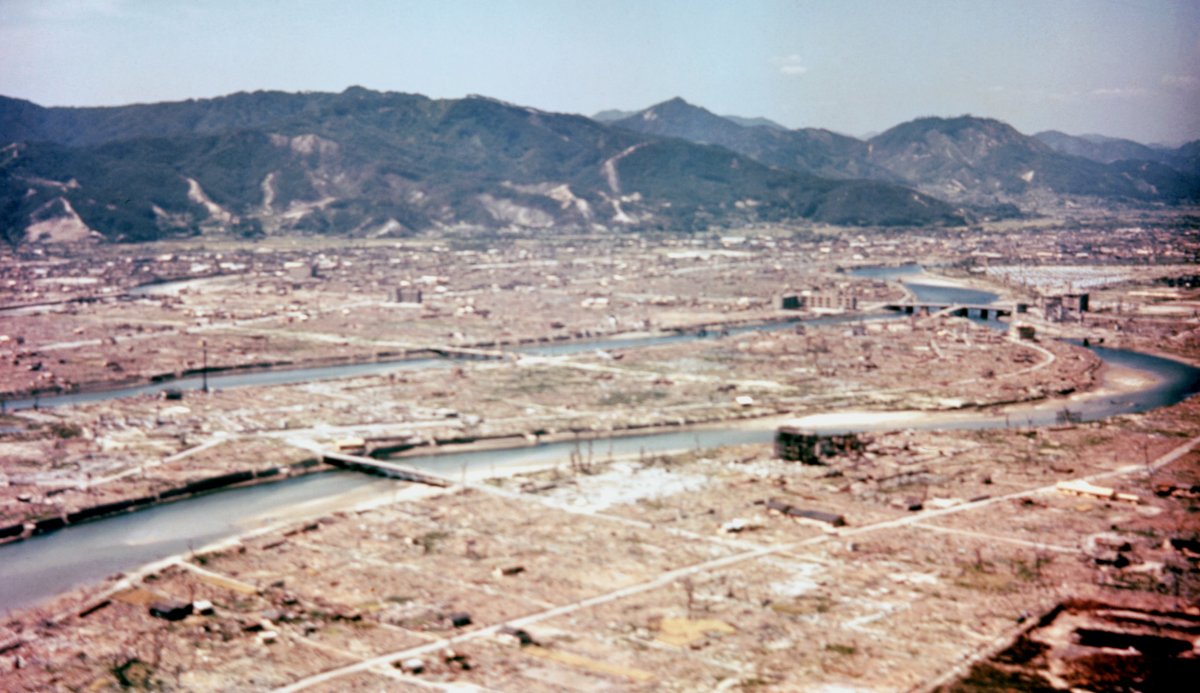

The first atomic bomb used in war was dropped near a downtown shopping district in Hiroshima, Japan, where metal arches formed a canopy of street lights over downtown shoppers and bicycle traffic. Survivors described eyebrows burnt away, skin hanging off faces, patterns from clothing seared into bodies, eyes popped out and intestines blown from stomachs. Three days after the August 6, 1945 destruction of Hiroshima, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

A Gallup poll taken in the same month as the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki reflected overwhelming support, with 85 percent of Americans in favor of incinerating the two Japanese cities and only 10 percent against.

Modern polling has found a gradual decrease in support for the bombings, from 59 percent approving in Gallup polling conducted in 1995 to 43 percent in 2016. CBS polling from 2016 found other sharp divides, with majorities of men and Republicans approving of the use of the atomic bomb against Japan and the majority of non-white, Democratic, women and young people disapproving. The Pew Research Center noted in particular a "large generation gap," with American 65 and older broadly approving of the atomic bombings, with less than half of 18 to 29-year-olds agreeing.

In Japan, only 14 percent of Japanese people agree that the bombings were justified, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center poll.

While the debate among historians over the American decision to drop two atomic bombs on Japan is primarily divided between "traditionalists"—who claim the bombing was necessary to save American lives—and the "revisionists" who argue the bombings were unnecessary, the substantial gap between older people's approval and younger people's disapproval has created an additional layer of disputation.

The result has been the emergence of a generational conflict narrative, which cites the polling trends against the bombings to suggest that the debate surrounding their necessity is itself a consequence of historical distance, hindsight and even "political correctness"—as a 2016 editorial in Forbes described the motives of those who disagreed with the "moral imperative" to decimate civilian cities. That year, Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, setting off a wave of editorials lamenting an "apology tour" second-guessing past decisions (though Obama did not apologize for the bombing). A Wall Street Journal editorial pushed back against what it described as an "increasingly common but misguided view that America shouldn't have used the atomic bomb."

But while the gap between American support immediately after and a comparative lack of support in the 21st century is notable, over-interpretation can obscure how divisive the bombings have always been. Even in the years immediately after, in the flush of victory and the post-war boom, widespread support for the bombings, which may have killed 210,000 people, dropped.

In 1948, a Fortune poll found that a scant majority, 51 percent, agreed that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki represented the use of atomic weapons in "just about the right way," with the majority more substantially entrenched when adding in the 15 percent of respondents who argued we should have used more bombs.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation attributes the drop in support to a better understanding of the destruction and bloodshed, with the New Yorker's 1946 publication of John Hersey's Hiroshima singled out for having a particularly powerful effect in turning Americans against the bombings. Still, only 26 percent of Americans were against destroying the two Japanese cities and their civilian populations, divided about evenly between those against the bombings entirely and those who would have preferred we had targeted an unpopulated area.

The public-facing response of the U.S. government in 1945 demonstrated an awareness of the potential for a backlash against the bombings, disputing the characterization of doubt as a modern phenomena or luxury. The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of History and Heritage Resources describes in detail the careful management of the public, contextualizing the "overwhelmingly favorable" American response to the atomic bombing of Japan "as filtered through the [Manhattan Project's] public relations efforts." On the Thursday anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, the New York Times published an article documenting the U.S.'s swift enforcement of a ban on photography showing the impact on civilians.

Anti-nuclear sentiment remained a pervasive concern of the U.S. government in the decades following, with presidential administrations even worrying themselves over pop culture depictions. In Neil Shute's 1957 novel On the Beach, cobalt-packed nuclear bombs devastate the northern hemisphere, leaving survivors in Australia no option except to wait for humanity's final destruction from the resulting fallout. Threatened by the 1958 launch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in London, President Dwight Eisenhower discussed with his cabinet ways to undermine the 1959 movie adaptation, fearing it could buoy calls to "Ban the Bomb."

While it's obvious that polling public sentiment can't tell us whether the annihilation of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and tens of thousands of humans was morally or strategically justified, it also can't be wielded in an attack on the legitimacy of that debate. Nor does it touch upon the many public officials who doubted the need for the bombing at the time and in the years after ("The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing," Dwight Eisenhower told Newsweek in a 1963 interview). Rather than representative of a new phenomenon, the polling only reveals shifts in a living conflict.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.