In the first episode of AMC’s new drama Dietland, a circle of muted, downcast women discuss their difficulty losing weight—in a group called Waist Watchers—when in bursts newcomer Janice (Bethany Kay), wearing a miniskirt, faux fur jacket, and green streaks in her hair. She’s there to see if shedding some pounds might help her back pain, and the group leader asks protagonist Plum Kettle (Joy Nash) to fill her in on the club’s mantra. “People don’t come to Waist Watchers because they feel good about themselves,” she dutifully intones. “They come because they’re ready to feel good about themselves.” Janice leaps out of her chair in disgust. “Are you kidding me?” she yells, as she heads for the door. “I feel good. I love myself…I am a goddess.”

The Hallelujah Chorus doesn’t play, but it’s strongly implied. At that moment, the show establishes its worldview: Fat people deserve self-esteem, too. That might not sound subversive, but if you’ve lived and watched TV as a fat person, particularly a woman, you know that it is. A 2009 study found that size discrimination in the U.S. had increased by 66 percent over the previous decade and was especially bad for women. We are refused service by salons, restaurants, and even gynecologists on the grounds of our weight.

Like all fat people, I'm constantly reminded of the ways society discriminates against us on a daily basis; it's exhausting and demeaning. At times, it takes all my mental energy to not go into a self-hating spiral, to believe that my worth isn't tied to my weight. Positive examples of fat representation (that is, women who accept and maybe even love how they look, who are treated with respect regardless of their size) are a rare commodity in our culture, but can provide a powerful antidote to the incessant negative messaging in the rest of the world. In Dietland’s adapted medium, television (the series is based on Sarai Walker's hit novel), fat women are usually relegated to supporting roles, turning up only to provide comic relief or to be a sounding board for the (model-thin) main characters, as if we need to squeeze into a size six before our stories are worth telling. While fictional men routinely time-travel across centuries to, say, battle intergalactic injustices, the idea that fat women might have lives and dreams of their own is often treated as an imaginative leap too far. In comparison, men rarely need to conform to any particular weight standard to take the lead on a show.

On the rare occasions when a fat woman is the star of the show, her body is almost always the focal point. On My Mad Fat Diary, Sharon Rooney plays 16-year-old Rae with compassion and complexity, but her weight is an enduring obsession. That’s relatable to anyone who’s ever struggled with self-acceptance, but nonetheless, it’s more of a painful representation of fatness than a positive one. While Lifetime’s Drop Dead Diva increasingly promoted body acceptance over its six seasons, its central conceit presented being fat—and, horrors, brunette—as an instructive punishment. After young model Deb (Brooke D'Orsay) dies in a car crash, she is brought back to earth in the body of fat, thirty-something lawyer Jane, played by Brooke Elliott. This means she has to not only become less superficial (because a bigger body is inevitably a downgrade) but learn to fight for her clients while battling new addictions to donuts and spray cheese. (I wish I were kidding.)

There are occasional exceptions: Donna Meagle (Retta) on Parks and Recreation was confident and respected, regardless of her size, although that would have been more impressive had the show not also had a local fast-food joint called Paunch Burger and constantly featured jokes about being the fourth-fattest town in the U.S. Melissa McCarthy played Sookie on Gilmore Girls, a woman with a full life, whose weight was never mentioned. But McCarthy then graduated to Mike and Molly, a show about a couple who met at Overeaters Anonymous and whose relationship was built around dieting.

More recently, everyone’s favorite family weep-fest This Is Us introduced us to Kate Pearson (Chrissy Metz), a character with few personality traits aside from being fat. While her siblings get juicy storylines focused on everything from interpersonal relationships to career achievements, she gets weigh-ins and endless angst about how her mom always wanted her to be thinner. And Kate will get thinner—Metz has revealed that her contract mandates she lose weight, which she claims not to mind, saying it will be a positive side-effect of Kate’s journey to “find herself.”

The life-changing possibilities of weight loss are also emphasized by competitive reality shows like Supersize vs Superskinny, My Diet is Better Than Yours, and The Biggest Loser, in which trainer Jillian Michaels’ encouraging mantras include “The only way you’re coming off this damn treadmill is if you die on it.” One contestant drank so little water that he pissed blood, yet we’re expected to see these programs as inspirational.

But what if you don’t have to lose weight to be happy? A pointed and sometimes surreal satire of the beauty, media, and diet industries, Dietland dares to suggest there might be another way. At the outset, Plum works out, prepares healthy crudités to eat later, and is underappreciated in her part-time gig at teen magazine Daisy Chain, where she ghostwrites an advice column for shallow editor-in-chief Kitty (Julianna Marguiles). Her only social activity is hanging out in her friend Stephen’s café, and she’s saving up for weight-loss surgery, which she’s convinced will change her life. So far, so typical for fat women on TV. But the difference is that Plum’s negative view of herself is challenged at every turn: by Stephen, her mom, sympathetic colleagues, and a flirty cop she meets in the lobby at work. “Doesn’t anyone ever tell you you’re beautiful just as you are?” asks Julia (Tamara Tunie), the manager of Daisy Chain’s beauty closet. At the same time, the show makes clear that Plum’s warped view of herself isn’t her fault but the inevitable result of a society where women are besieged by the exaggerated promises of weight-loss gurus and non-stop negative messaging about being fat.

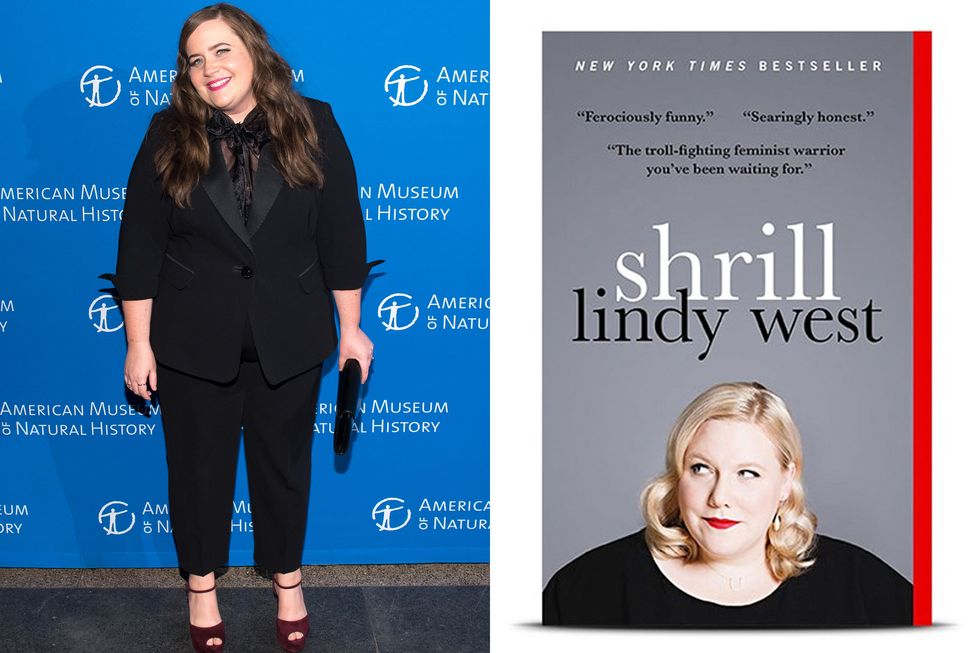

Plum might not start out loving herself or her body, but from the show’s point of view, there’s no reason she shouldn’t. That’s a perspective rarely expressed in pop culture, but it’s gathering pace. Last month, Hulu announced that it’s turning Lindy West’s bestselling memoir Shrill into a sitcom starring Saturday Night Live's Aidy Bryant. The comedy will center on a fat woman who wants to change her life—but not her body. Stories like these have rarely made it to screen. One of the few that did, State of Georgia, was supposed to be about a plus-size woman with a big personality, but when Raven-Symoné was cast, she ended up losing a lot of weight before filming, which muddied the fat-posi message.

We can’t blame the historically poor televisual representation of fat people for real-world discrimination. But negative portrayals and a lack of visibility in entertainment do contribute to a hostile climate and perpetuate the idea that it’s acceptable to ignore or mistreat us, with one study suggesting mass media has more of an impact on how women feel about their bodies than the opinions of family or friends. Seeing a range of body types in film and television might normalize the idea that fat people exist and help us to feel less alone. If nothing else, it would better reflect a society in which more than two in three adults are fat. Some people will always see fat characters as “glorifying” weight gain but given that fat-shaming and the majority of diets have been proven not to work, maybe it’s time to encourage acceptance.

Audiences seem increasingly open to watching fat women, including those who aren’t desperately trying to change. In a second season episode of anthology series Easy called “Prodigal Daughter,” Danielle Macdonald plays Grace, a high school senior who is fat but not worried about it, humiliated for it, or rejected because of it. In fact, it’s never mentioned. She’s bright and well-liked, with friends, a boyfriend who loves her, and teachers who respect her. When her parents tell her they’re proud of her, there’s no lingering “but…,” no disapproving glance at her body or sad shake of the head. I kept watching, waiting for the fatphobic other shoe to drop, but it never does. Instead, the show upends every tired trope about fat women and provides a template for portraying us as fully human. It’s just one episode, but it gives me hope for a more fat-positive future, in real life and on television. It’s a revelation. If the trend continues, it could be a revolution.