Robert Sikoryak has inadvertently hit upon a fundamental contradiction in the Apple brand. “I’m a big fan of Apple,” the 52-year-old cartoonist says, smiling above a plate of Mexican food in southern Manhattan. “And the thing that’s fascinating to me is that the products are so built on the design, the elegance, and the beauty; but the text, the terms and conditions, does not” — and here he waves his hands like a crossing guard telling you to halt — “have that design beauty.”

Sikoryak, better known by the abbreviation R. Sikoryak, has set out to fix that state of affairs. The veteran writer and artist has just released a remarkable comic entitled Terms and Conditions: The Graphic Novel. It more or less does what it says on the tin. Over the course of 103 pages, Sikoryak illustrates the entirety of the iTunes terms and conditions as of October 21, 2015. He’s taken the 20,699 words in that labyrinthine text and made them enjoyable, by turning them into narration and dialogue for an epic saga that spans more than a century of comics history. The narrative conceit is that the reader is watching the adventures of Steve Jobs, as he dictates the terms and conditions to anyone who’ll listen.

But far more interesting is the stylistic conceit. Sikoryak is famous for his gift for imitation — in the pages of Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s famed alternative-comics anthology Raw and various other outlets, he’s penned adaptations of great works of literature done in the style of various classic comics — Beavis and Butt-head are combined with Waiting for Godot, say. (More recently, he’s gained acclaim for putting Donald Trump’s words into renditions of old comic-book covers.)

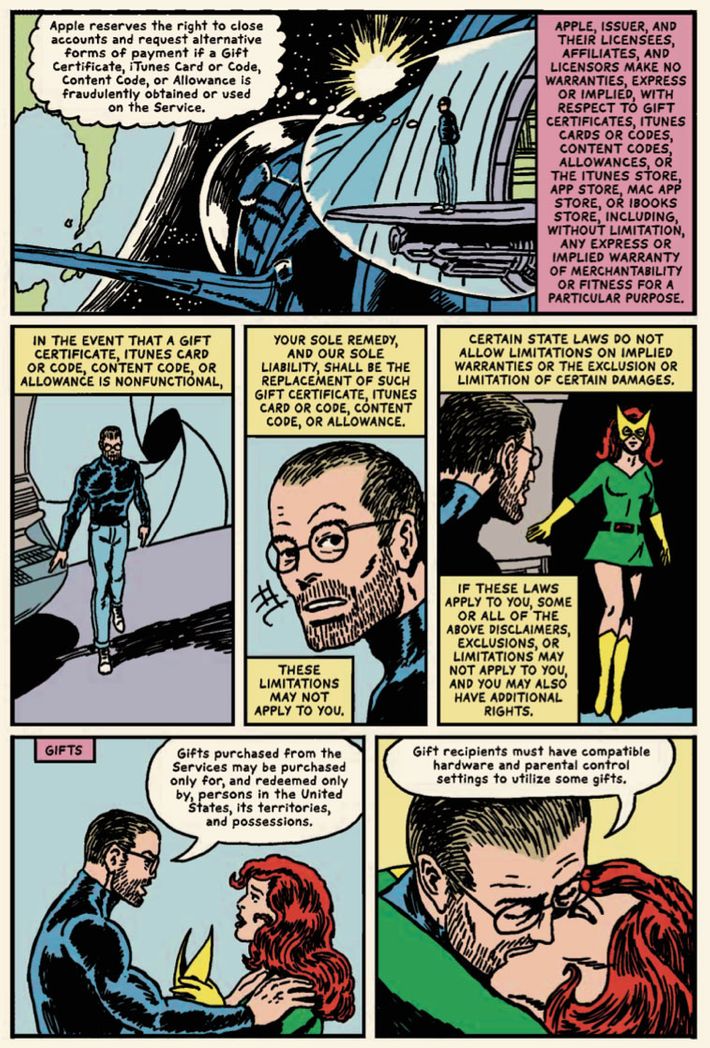

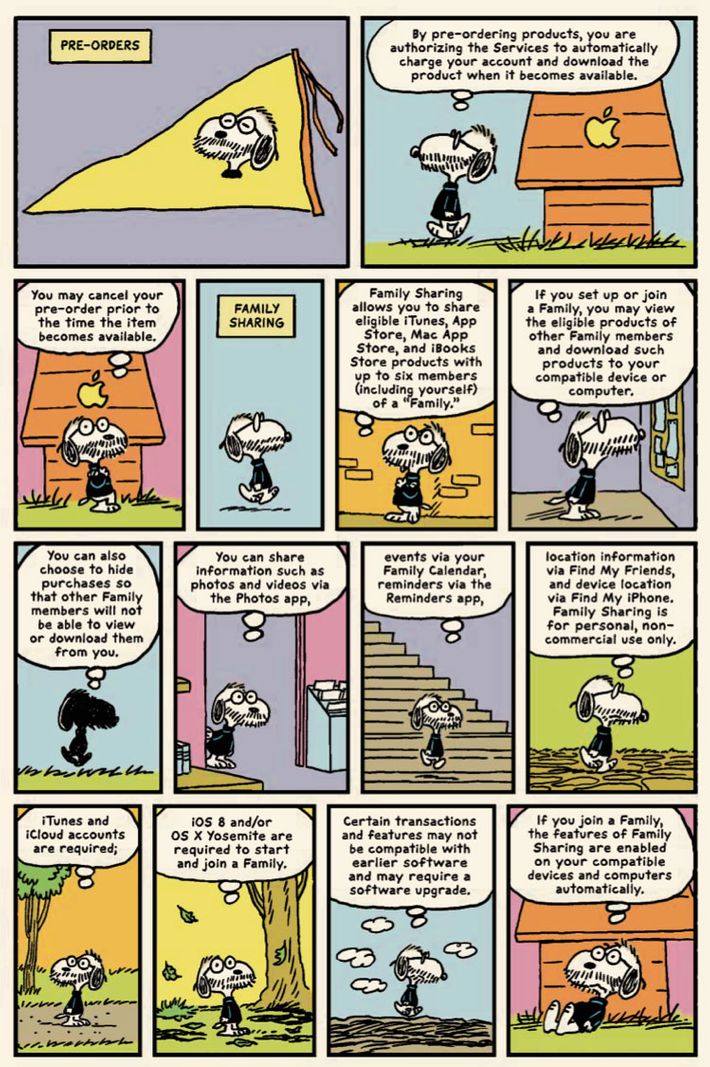

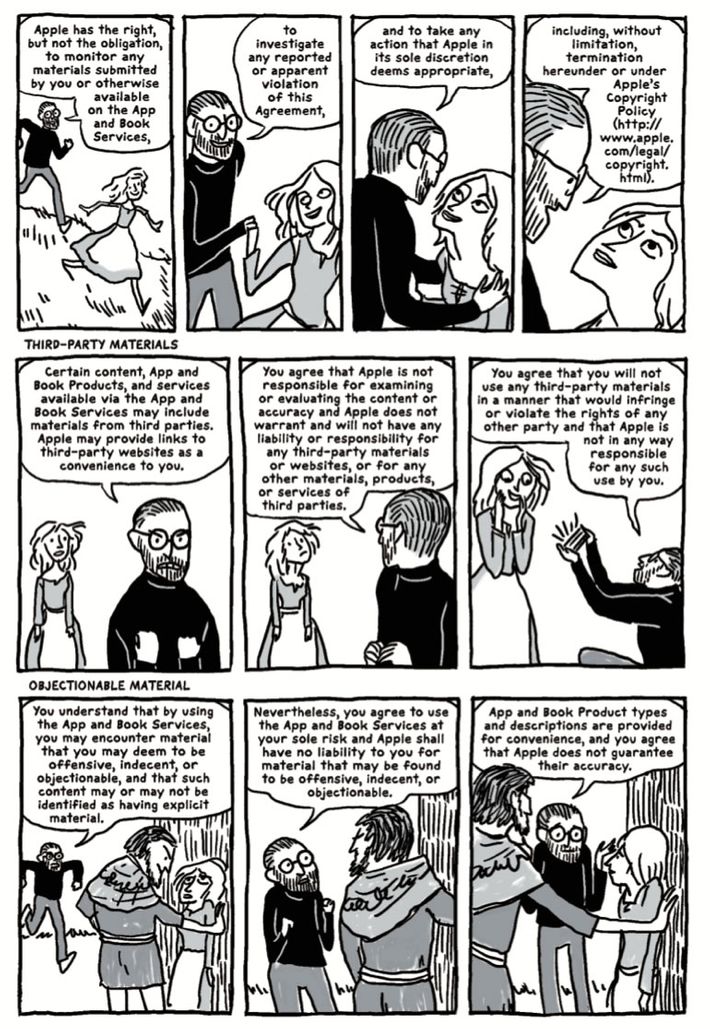

Here, he’s taken that mimicry farther than it’s ever gone. Each page of Terms and Conditions is done in a pitch-perfect pastiche of a different page or set of strips from a great comics artist. “An HDCP connection is required to view content transmitted over HDMI,” a petite Jobs drawn like Richie Rich tells a child companion. An androgynous youngster wanders into an ornately drawn home office and sees Jobs sternly gazing at his laptop, while the disclaimer of warranties and liability limitations is narrated, and we instantly recognize the work of Alison Bechdel in Fun Home. Jobs kisses Jean Grey just before she dies in the X-Men’s “Dark Phoenix Saga,” while he passionately whispers, “Gift recipients must have compatible hardware and parental control settings to utilize some gifts.”

Peanuts, Watchmen, Dick Tracy, Edward Gorey, Persepolis, and even My Little Pony appear, all of them rendered with stunning and reverent skill. It’s entirely unclear how the reader is intended to react to any of this, as it’s unlikely any comic like this has ever existed. Are you supposed to read the pages in order? Are you supposed to read them at all, or just look at them? Is there a hidden meaning that comes up if you pore through every stultifying word in the text? Is it a commentary on Apple? Most important: Why on earth would someone make this thing?

Sikoryak is fine with the ambiguity, but is also happy to explain the surprisingly simple story of how Terms and Conditions came to be. In short, it was done as a personal challenge, and an attempt to adapt to the current comics gestalt. “Usually, what I do with my work is, I take long pieces of literature and compress them into small, short comics,” the wild-haired, compact, and Hawaiian-shirted Sikoryak says. “But because of the development of graphic novels over the last two decades, I felt like I wanted to try something long. I was just sort of casting about for a long piece of text that I could use. And ultimately, when I thought of long piece of text, the terms and conditions just popped in my head.”

Though Sikoryak is a longtime Apple user — he entered the House that Jobs Built when he bought an iMac in the late 1990s — he, like all of us, had never actually read the T&C document. I mean, Jesus, can you think of anything more boring? So he developed a strategy to liven it up for himself and others. “Once I thought of doing this long text, it was like, How can you make it interesting?” he recalls. “The great thing is, there’s no plot. There’s no narrative. There’s a lot of nonfiction comics that are very literal-minded and show people talking to the reader and pointing at objects, and then there’s a word balloon explaining what they’re pointing at. I didn’t want to do something that earnestly square.”

Instead, he just amped up his talent for aping and opted to imitate as many artists as he could think of. When he began, he figured the tale would run about 70 pages, and he mapped out his artists accordingly. As he moved along, he discovered he had estimated poorly and would require more space; to make matters worse, Apple expanded the T&C while he was in the midst of the process. More and more artistic templates were needed. Sikoryak slaved away, transforming his brain and hand with each new page. The art wasn’t put in any kind of chronological or thematic order, meaning he would leap from the cartoony to the detailed, the archaic to the ultramodern, from one exercise to the next.

The finished product is remarkable for a few reasons, one of which is the statement it makes about how utterly inaccessible the text is, even when it’s put into the thrilling visual tradition of comics, and even when it flips between various styles at ADHD-addled speed. Your eyes still glaze over at every attempt to process the English that you’re reading, which is a shame, given that your lack of knowledge about it could send you to court and drain you of your cash. Deliberately or not, Apple has made you a serf to a lord whose language you don’t speak.

By creating this book, Sikoryak has unwittingly stumbled into a vibrant discussion about how to apply design principles to T&C agreements. Savannah College of Art and Design student Gregg Bernstein made waves in 2011 by collaborating with legal scholars to create a more eye-friendly approach to such documents, the 2013 documentary Terms and Conditions May Apply harshly judged the unfairness of using Byzantine language to protect corporations at the expense of educated consent from users, and the browser extension Terms of Service; Didn’t Read overlays simple language onto T&C verbiage, so you can know what you’re getting into. Similarly, Sikoryak is seeking to make people engage with legal language in a way that doesn’t bore them into submission.

That said, the artist says he wasn’t aiming to make a critical statement, and he bears no ill will toward Apple (and, for what it’s worth, they’ve never reached out to him, so perhaps their litigiousness isn’t as threatening as it appears to be in the T&C). He also didn’t deliberately set out to have you see any connections between a given section of text and the visuals surrounding it — but that doesn’t mean there aren’t connections to be found. Terms and Conditions ends up being a fascinating little experiment in cognition, where the random placement of words next to images leads you to start surmising what the juxtapositions could mean.

To wit: a page done in the style of Kate Beaton lifts three of her comic strips about medieval peasants, and a panel in which Jobs proposes marriage to a fair maiden is accompanied by text about agreements. A page taken from a comic about a superhero who is, in reality, two individuals bound to one another, begins with phraseology about “an inseparable part.” It’s all accidental, but you start to wonder what it is about human thinking that tries to find connections when there are none.

But beyond the mental gymnastics and artistic ambition lies Terms and Conditions’ most salient and inspiring feature: its ecumenicalism. Comics is a hopelessly divided medium, in which the superhero fans dislike the anti-superhero snobs, younger fans find old comics hard to process, manga fans eschew Western products, and there’s an overall sense that there are literary comics and pulp comics, and never the twain shall meet. Sikoryak expertly dispels that notion by throwing more than a hundred years’ worth of words-and-pictures storytelling into a salad, and declaring that it’s all delicious. The early-20th-century newspaper strip Little Nemo in Slumberland coexists with the sexy, modern work of Saga artist Fiona Staples; Garfield is on par with the pioneering Will Eisner; Hyperbole and a Half is granted equal weight as R. Crumb; and so on.

Terms and Conditions is, in other words, a declaration that there is more that holds us together than keeps us apart here in the gutters of comics. That’s appropriate, given the subject matter — after all, Apple products are (for better or worse) a common denominator between classes, races, and nations. We all accept the terms, and we all live under the conditions. That kind of can’t-we-all-just-get-along openness was very much part of the plan for the cheerful and charming Sikoryak when he set out to make his unprecedented tome. “I just wanted to make sure that, if you only knew five comics, you might know something in this book,” he says. “I wanted people to go, Oh, I know that! There’d always be something there for them to go, Oh, this is familiar! I’ve always wanted my work to give people a hook that they could approach, even if it might become bizarre. Or, in this case, impenetrable.”