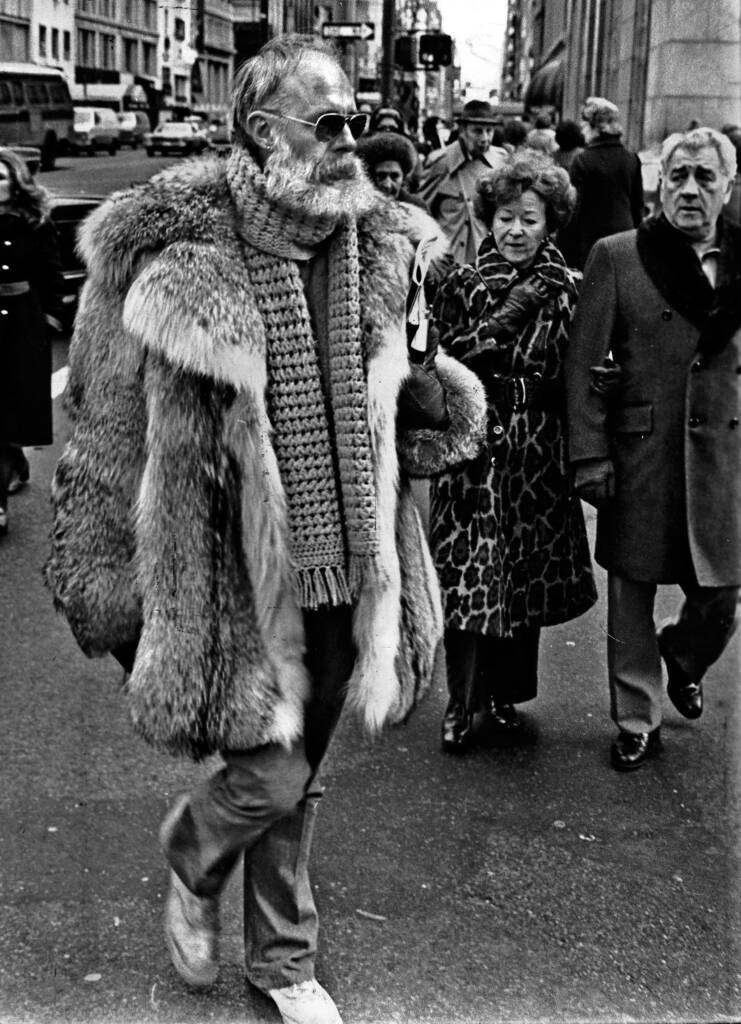

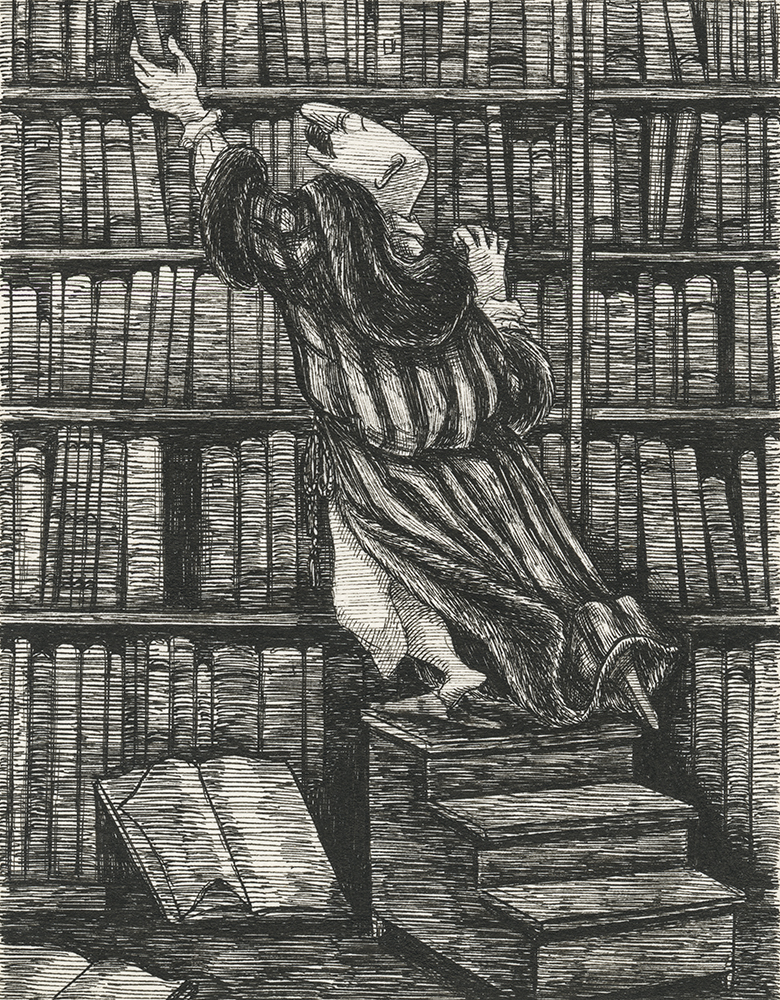

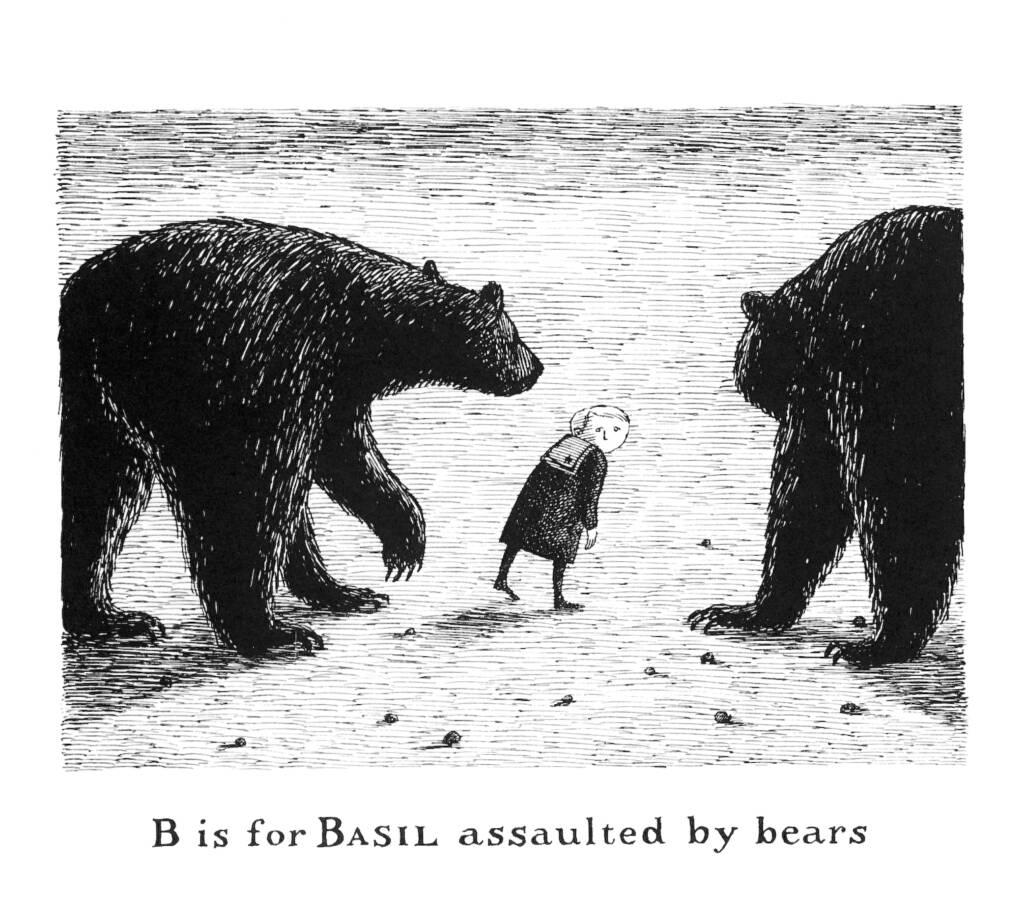

Gorey attended Harvard University from 1946 to 1950, majoring in French literature, studying with John Ciardi, and rooming with the poet Frank O’Hara. Gorey’s earliest illustrations date from this period, when he also designed sets, directed, and wrote for the Poets Theater, along with O’Hara, John Ashbery, Alison Lurie, and Violet Lang, among others. His eccentrically dressed persona – long overcoats, tennis shoes, clanking jewelry, and eventually a luxuriant beard – was established at Harvard. In 1952, Gorey moved to New York to work in Doubleday’s new Anchor Books division, eventually designing more than fifty distinctive covers and achieving recognition for his illustrations. He worked for various publishing houses until turning freelance in the mid-1960s. He also began writing and illustrating his own books, publishing in 1953 the first of what would be more than a hundred small, enigmatic volumes: The Unstrung Harp, the illustrated story of the travails of a novelist. While Gorey claimed that he knew nothing about being a writer at the time, Graham Greene called The Unstrung Harp “the best novel ever written about a novelist and I ought to know.” Partly because of the introductions to the Public Television series Mystery!, created with the animator Derek Lamb and his team in 1980 and still in use, Gorey is best known to the wider public for his drawings. In his books, which chronicle a vaguely Edwardian world of patriarchs in ankle-length overcoats, mustachioed men in padded dressing gowns, wantons with nodding plumes, uniformed housemaids, and children in sailor suits and pinafores, images carry the ambiguous narratives as much as the text. His often relentlessly cross-hatched, inventively patterned pen and ink drawings can be obsessively detailed, full of small events that we must work hard to discover, or, as in the 1963 masterpiece The West Wing, which is devoid of text,miracles of suggestive economy. Yet Gorey always depicted himself as a writer, not as an artist. He described his books as “Victorian novels all scrunched up.”

In New York, Gorey soon became a passionate admirer of the New York City Ballet and George Balanchine, whom he described as “the greatest influence on me…Everything he ever said about art, in the larger sense, was only too true.” Gorey attended every performance of all of Balanchine’s ballets until the choreographer’s death in 1983. That year, Gorey, who had divided his time between midtown Manhattan and Cape Cod, summering with family, moved permanently to the Cape, “an act of aestheticism worthy of Oscar Wilde,” according to Stephen Schiff in a New Yorker profile.

An equally important New York connection was with the Gotham Book Mart, where Gorey became a close friend of the founder Frances Steloff and her successor Andreas Brown. Gotham Book Mart became a main source for Gorey’s books, especially after 1962, when he established his private imprint, The Fantod Press; Gotham occasionally published his books, arranged for him to illustrate works by Samuel Beckett and John Updike, among others, and showed his work regularly in the bookstore’s art gallery, including his limited edition prints, especially those made in the 1980s and 1990s, when he worked extensively with the Brewster, MA, printmaker Emily Trevor.

Gorey remained irredeemably American. Despite the apparently English setting of many of his books, his only trip to Europe was to the Scottish islands, the Shetlands, the Hebrides, and the Orkneys. He described not seeing the Loch Ness monster as the great tragedy of his life. But his international reputation steadily grew, as books were translated. In 1972, Amphigorey, an anthology of fifteen works, was published, followed, over the next few years, by Amphigorey Too, Amphigorey Also, and Amphigorey Again. Gorey’s long interest in book design led to his experiments with unconventional formats, including miniatures, pop-up books, postcards, and collections of moveable parts.

A voracious reader and collector of everything from obscure Victorian novels to translations of The Tale of Genji, from Symbolist poetry to books on napkin folding to the works of Carl Jung and George Gurjieff, and, apparently, everything in between, Gorey was also a connoisseur of popular television programs and obscure films. He had encyclopedic knowledge of Japanese cinema and the work of pioneers such as Louis Feuillade, the inventor of the serial thriller, whose silent films, such as the Fantomas series, clearly inform Gorey’s interiors and street scenes. He seems to have so thoroughly internalized an astonishingly wide range of sources that we can find allusions in his books to the works of Max Ernst, Paul Klee, police photographers, and 19th-century illustrators, along with flavors of Buster Keaton’s films, Lewis Carroll’s and Ivy Compton-Burnett’s books, Kabuki theater, and much, much more, including parodies of Agatha Christie’s mysteries and the pseudonymous French pornographer Pauline Réage’s The Story of O. Gorey claimed that he knew “a little bit about a lot of things,” a disclaimer that belied his extraordinarily well-furnished mind and his depth of knowledge of recherché subjects.

Gorey had been interested in theater since his Harvard days and became involved in New York off-Broadway productions based on his work, while mounting his own experimental plays, with amateur actors and sometimes puppets, on the Cape, during the summer. In 1973, a production of Dracula that he designed for a small Nantucket theater attracted enough attention that in 1977, it opened on Broadway as Edward Gorey’s Dracula – a Tony award-winning success that ran for almost three years and toured internationally. In 1979, the royalties from Dracula permitted Gorey to purchase a two-hundred year old sea captain’s house in Yarmouth Port, MA, his home for the rest of his life. It was filled with a constantly growing collection of more than 20,000 books, finials, odd bits of iron, rocks, and miscellaneous flea market finds, along with a carefully selected collection of paintings by Albert York, drawings by Balthus, Pierre Bonnard, Charles Burchfield, George Herriman, and Édouard Vuillard, photographs by Eugène Atget, and 19th century sandpaper pictures, all of which reverberated in various ways in his own work.

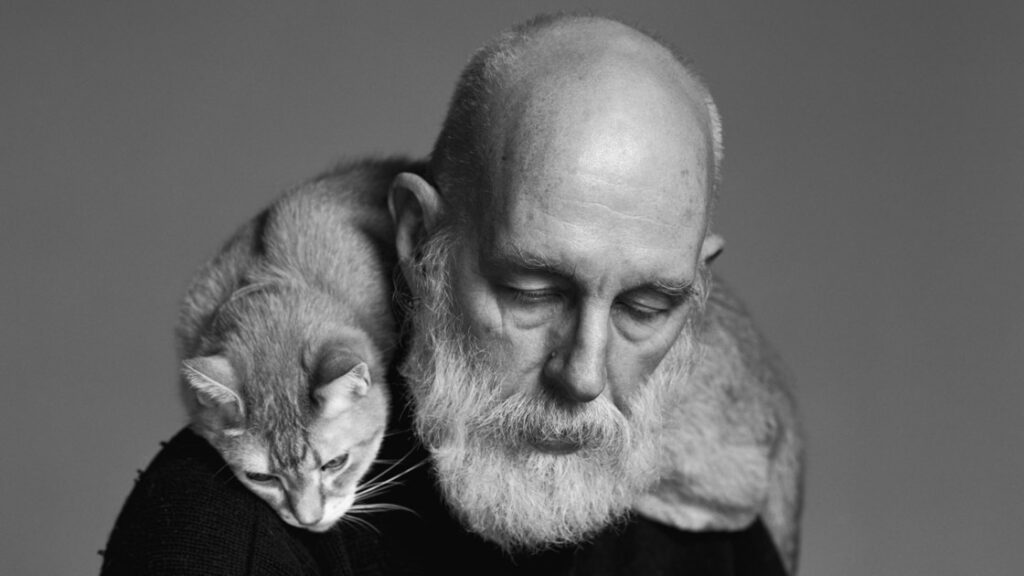

A dedicated animal lover and advocate of animal welfare, Gorey described himself as a Taoist and would move worms off of wet pavements, to keep them from being stepped on. He lived life-long with multiple cats. “It’s very interesting,” he told an interviewer, “sharing a house with a group of people who obviously see things, hear things, think about things in a vastly different way.” Gorey left his estate to the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust, which contributes to agencies supporting the welfare of cats, dogs, whales, birds, bats, insects, and invertebrates. After his death in 2000, at 75, Gorey’s Cape Cod home on the Yarmouth Port Common was converted into the Edward Gorey House, a museum whose profits and programs benefit animal rights and literacy programs. It is open from mid-April through December with an annually changing exhibition and permanent displays. A poison ivy vine that infiltrated a living room window casing during Gorey’s occupancy of the house has been removed.

Karen Wilkin

New York, June 2021