Art In Conversation

Fred Tomaselli

The Brooklyn Rail visited Fred Tomaselli’s studio in the heart of Williamsburg on a cold November afternoon. Up one flight of stairs off Driggs Avenue, the studio is modest and efficient, like a serious medieval workshop. Three new paintings lined one wall. During our talk his assistant, Casey Loose, quietly glued photos of mushrooms on the foreground of a giant new work lying face up on saw horses. Around us the studio tables were crowded with sheets of cut-out collage items— sheets of plant leaves, photos of noses, eyes, human hands, birds, and flowers lay in separate piles. Fred showed us filing cabinets filled with bottles of pills and medicines ready for use.

Chris Martin (Rail): So, let me ask you about your connection with Brooklyn. I know you’ve been a part of the Williamsburg art scene for a long time.

Fred Tomaselli: Yeah, I moved here in 1985. I found and fixed up a little 325 dollar a month storefront in Greenpoint and started working…

Rail: Those was the days of Minor Injury gallery.

Tomaselli: Yeah, they were a lot of fun and right down the street.

Rail: You knew Joe Arnheim from California?

Tomaselli: I knew Joe long before he opened up Pierogi, when we both lived in downtown L.A. I had gone to Cal State and moved to downtown L.A. in 1982 with a BA in painting and drawing. I then promptly abandoned painting and drawing the next year and basically focused on installation and site specific work. I was doing shows with the likes of Charles Ray and Paul McCarthy and was very hooked in with the punk rock and art scene. I had basically given up on painting at that point because I couldn’t figure out a way to get out from under its burden of history. I guess I just didn’t really know what paintings could do. I had a crisis of faith and I even gave up art altogether to put out punk rock magazines for a while.

Rail: So what brought you back to making specific objects again?

Tomaselli: I just ran out of things to say with the installation work. I was making low-tech installations that were accumulations of found objects and electronics that referred to theme parks…

Rail: Theme parks, you mean like Disneyland?

Tomaselli: Yeah, I grew up next to Disneyland.

Rail: What a lucky kid. So was that a formative influence?

Tomaselli: Yeah. Going to Disneyland and then happening to go into a Bruce Nauman retrospective is a good indication of the dichotomous level of my formative growth [laugh]. Also, LSD had been a formative influence on how I saw the world. I was making these works based on theme parks with light trapping corridors that expanded into larger rooms. The subject of the works were their own artificiality and the mechanics of perceptual modification.

Rail: Which are very much themes in your paintings now.

Tomaselli: Yeah, what happened was the installation format seemed to have run its course and my work kept getting flatter and flatter, and I started thinking about the pre-modernist ideal of painting as a window into an alternate reality. I started seeing lots of comparisons between the utopian aspects of art and the utopian counter culture and also seeing the dystopic side as well. I felt that painting could be both a window and a mirror to the world. It’s important to remember that I entered the art world as it was imploding into post-modernism and I was coming into the counter culture as it was collapsing into disco and cocaine. There was all this failure and loss of idealism and I was interested in digging through the rubble to see if there was anything worth keeping.

Rail: The art world was ruled by cynicism. Painting was discredited. You were coming in investigating utopias when everything seemed hopeless…

Tomaselli: Yeah, It didn’t go well at first, which made me feel like I was on the right path. I really was pretty alienated from the art world discourse— it seemed like so much arid theory for disembodied heads that had nothing to do with life. I didn’t want to make art if it had to be like that.

Rail: When did you first collage actual drugs into your paintings?

Tomaselli: In 1989. It came out of my life experiences. My friends were dying of AIDS and taking masses of pills. I mean at the time I started making this work, drugs had morphed from agents of enlightenment and pleasure, to tools of survival. There was the rubble of the visionary quest that devolved into Studio 54 while the terror and enslavement of the crack epidemic raged through this crime ridden city… I was trying to figure out if there was anything worth saving in all of that. That’s sort of what got me into doing it and part of it was self consciously searching for a new way to make painting. I wasn’t disregarding my own doubts but I was going ahead and doing it anyway. I was trying to put the contents of my personal life into the work in an attempt to talk about something bigger.

Rail: You were wrestling with doubts about making paintings at all?

Tomaselli: Right, These weren’t paintings originally. They were assemblages of objects that were made to look like paintings. I’ve only recently been comfortable with talking about myself as a painter.

Rail: So you set down the pills or whatever— fix them to the wood support— and seal them in place with resin. You have built this complex system of collage. Tell me how this evolved.

Tomaselli: I started originally with aspirin, Sudafed, stuff like that— then I needed to throw some subcultural drugs in there because I think it’s all about the same thing; relief from pain, pleasure, desire, altered consciousness… So I started to put pot leaves from my garden into my work and that opened up the dreaded nature/culture dialogue. The leaves put the shape of nature into the work, which softened things up in the context of the hard, manufactured geometries of the pills. That lead to the addition of the collage elements—cutting out pictures of bugs, birds, flowers and body parts from magazines and field guides. I then encased all this ephemeral material in resin.

Rail: You’ve used real bugs as well.

Tomaselli: Yeah, that started when I was living upstate one summer in Sam Messer’s place and there were so many bugs! All these tent caterpillars were hatching into moths that landed into my work. I was pouring all these resin pieces in this barn and no matter what I did, they’d fucking land, stick and die in it. So I decided to go with it and work outside. I’d hang these huge lights on the pieces at night and create these bug storms— when they were at their peak I’d pour resin down on the work and they would stick and die in these random formations. It was a collision of nature and technology, letting chaos and chance put them where they were. I thought of them as portraits of the atmosphere— as a basis to make landscapes with the real bugs as actors in the work. The event would last about an hour, but afterwards, I would work for months to make them beautiful.

Rail: You first became acknowledged as the guy that puts real drugs in his paintings. Did you ever find yourself in trouble for exhibiting marijuana and drugs?

Tomaselli: Not really. This isn’t an attempt on my part to be transgressive or to push anybody’s buttons. This is work that comes out of the way my life is. If I can make a life in the anonymity of the art world, that’s all right with me. In a funny way, I’ve destroyed the drugs, or at least rearranged their use value. In my work, they travel to the brain and alter consciousness through the eyes.

Rail: There were no legal problems?

Tomaselli: I’ve had some issues come up. Once, I think 1994, the works were temporarily arrested in Paris by customs but were eventually released from the contraband prison. It was funny—I had an opening with no art in it. I showed at a gallery that was associated with a lot of conceptual art, so showing an empty gallery was initially interpreted as a Yves Klein style statement of the futility of art making. I was saying, "No, I make paintings but they’re locked up in customs," and they were like, "That is so boring, you are so boring." [laughter]. There have been a few institutions that have tried to purchase my work that encountered a board of directors that felt they could get in trouble for it. By the way, I don’t consider it my right to have my work purchased by museums—if they think it’s too controversial, that’s fine...

Rail: Most artists of our generation grew up surrounded by drugs. I think many of us were changed by our use of psychedelics. For me they helped open up a visionary world— a spiritual dimension. That was true of so many friends and contemporaries, and yet few of us put it directly into the work. I am really struck by how you made it the subject and content of your painting, which seems such an obvious but wonderful thing to do.

Tomaselli: Well, it came to me from a lot of different angles. It is one of the great repressed discourses in contemporary culture— this massive effect of psychedelic drugs on consciousness and its tremendous effect on American culture. But it’s not talked about all that much.

Rail: Not only are you putting actual drugs into the paintings, but there’s a conscious depiction of psychedelic vision.

Tomaselli: More and more so— yes. It’s a complex fusion. I think of my work as truly hybrid in that it’s made of photographs, objects and paint cohabiting different levels within the same picture plane. It’s hard to tell what’s what.

Rail: A physical hybrid of materials?

Tomaselli: It’s a physical hybrid and a historical and stylistic hybrid. I’m borrowing from lots of different cultures and traditions, many of which are enemies to one another. I get a lot of juice from Asian art, German Romanticism, Pop, Conceptualism and so on and so forth, but also, and very importantly, my brain has been hybridized by the use of hallucinogenic drugs. [laughter] These works reflect a mind that has been conceptually, psychologically and perceptually altered from the use of these substances. I consider myself to be a hybrid creature. LSD has colonized part of my DNA and I’m trying to put that into my work.

Rail: Are you talking about an openness to a certain kind of visual phenomenon? An openness to psychological and art historical influences?

Tomaselli: Well, initially my work was an illustrative manifestation of conceptual concerns that ended up looking quite minimalist. One of the ways I’ve tried to push it is through the addition of decorative intensity. I never really throw anything away, I just keep adding things. There’s been so much information piled up on itself that it has become hallucinogenic. My personal doors of perception have been opened on occasion to really allow the full throttle world to enter my psyche. My work is the culmination of this multiplicity of information— all the histories that I’ve been accruing.

Rail: Do you still use hallucinogenic drugs?

Tomaselli: I haven’t taken LSD since 1980. I think sometimes you need to remove yourself from intense experience and get some distance to really use it as subject matter. So my heroic doses of LSD are long over.

Rail: Well, you must be completely concentrated and alert to make these paintings— they are very carefully made, amazingly labor intensive objects. How did you come to work on this tiny scale? This exploration of minute detail emerged with a number of artists in the 1990s, I’m always impressed with that kind of skill— you and people like James Siena using these tiny brushes.

Tomaselli: Well, I met James in L.A. before I moved to New York and he got me a job working with him at a frame shop. At the time there was this simple notion that concept and execution were mutually exclusive activities, that great artist’s thought great thoughts and had them fabricated by underlings. James and I were these low end workers of the art world and I guess we were fairly suspicious of this dismissal of craft. I felt that the process of making art was integral to it’s meaning and in order to see the art I wanted to see, I had to make it.

Rail: I heard James describe himself as just a humble craftsman.

Tomaselli: Oh, he’s much more than that.

Rail: I know he is. But he’ll talk about how he wants to be like this anonymous guy putting tiles in the Taj Mahal. You both have developed this high level of detail and craft. Ultimately it seems to be about a loving kind of attention— your commitment to your own vision. Does that connect with psychedelic vision? Is it a William Blake thing that God is in the details?

Tomaselli: The interesting thing about psychedelics and pop culture is that psychedelia did open me to investigate a neglected art history though the back door of its own self-generated kitsch. It allowed me to really get turned on to everything from Asian art to William Blake. It tweaked my vision to deep structure. I think one part is the psychedelic experience and one part is the world that psychedelic drugs directed me towards.

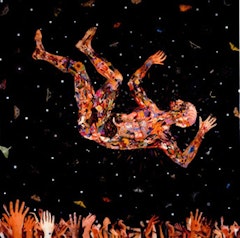

Rail: Let me ask you about these new paintings here in the studio. These figures are composed of hundreds of collaged birds and body parts and everything.

Tomaselli: I began working with these Arcimboldo-inspired figures for the show with Harry Smith and Philip Taaffe and now it’s just taken over my work. I’m kind of finding my way back to figurative-narrative art, which is a place I rarely visit.

Rail: This image of a falling man above these hands?

Tomaselli: It’s a mosh pit situation— transcendence— oblivion— the modern sublime.

Rail: So there’s a narrative there?

Tomaselli: I hope I’m not telling stories the way a writer would. I think art should be somewhat ambiguous because an easily digested narrative gets exhausted too quickly to look at every day. But whenever you put in a figure, people start to read narrative into it—at least that’s what I’m finding out.

Rail: Well, these paintings look terrific.

Tomaselli: Thanks. But you know, I think its just getting closer and closer to how the world feels being processed through my personal nervous system. I’m feeling less and less articulate about the specificity of the work. I guess that all the initial conceptual strategies are still somewhere in the work, but they mean less and less to me. I’m not to sure what these new works mean, but I’m doing them anyway. I probably shouldn’t even consider myself a conceptual artist anymore. I make pictures— that’s it.

Rail: That sounds very healthy. I used to think of your earlier work as more abstract. Does this distinction between abstraction and figuration mean anything to you?

Tomaselli: It never has had any meaning for me. I’ve always put at least one figurative work into every show and I always mix it up with landscape and abstractions. I’ve looked at these shows as a disassemble figureground, micro-macro universe. This is the first time where I’ve embarked on a body of work that has a unified formal common denominator. I hope it’s not to boring or repetitious. They come out of my love of Renaissance Painting, the work of Blake and especially Tibetan Tongas with their preoccupation with the Corporeal aspects of the body— with decay and death. I live with an 18th century Tonga and it’s probably unduly influencing me, or maybe it’s my obsession with Appalachian Death Ballads, I don’t know.

Rail: Are you involved with Tibetan Buddhism as a practice?

Tomaselli: No, I’m like everyone else in the art world— I’m Buddhist friendly, which is such a wimpy position. I’m not like Alex Gray who is totally committed to it. I’m very sympathetic to the Tibetan view of the cosmos but I’m just not ready to throw my allegiances to any one particular ideology. I’m afraid of becoming too sure of things— too orthodox.

Rail: I think that’s important to separate spirituality from religion. They sometimes coincide but they often don’t.

Tomaselli: I’m uncomfortable with the term "spirituality." It seems like it’s a catch-all for whatever people want their feel good stuff to be. So much of it is so narcissistic and being from New Age California, I have a slightly jaundiced view of that. My work is based on a certain amount of skepticism. I can’t seem to get behind any particular program.

Rail: So let me ask about Alex Grey. Your paintings are reproduced along with his in this wonderful new book about Psychedelics and Buddhism, Zig Zag Zen. Do you have a dialogue with him about psychedelics?

Tomaselli: Yeah, me and him are friends. I’m a huge fan of his work and I think we have some parallels and a good dialogue between us.

Rail: But he is so earnest about his spirituality. There doesn’t seem to be any skepticism.

Tomaselli: Alex is a true believer. Alex believes that psychedelics are a short cut for humans to complete their spiritual evolution on earth. But he’s not some proselytizer— he’s quite tolerant about different beliefs and pathologies. He is a true believer where I am a sympathizer. We’ve both come through these psychedelic experiences that have influenced our work and we’ve both looked at a lot of Tibetan art and other similar works.

Rail: Fred, I can remember seeing paintings of yours which had a sunset landscape underneath this psychedelic patterning of pills. I thought that some of those paintings were the best visual illustration of actual psychedelic vision. They had that sense of looking at the landscape and seeing a dancing tracery on top. With certain psychedelics that’s very much what happens— there is this overlay of a pulsing patterning on whatever it is your seeing. Were you conscious that your paintings were illustrations of that?

Tomaselli: Well, I was. I think that the first time I really saw the world through an actual scrim of other information was under the influence. It was later that I began to see nature itself through a scrim of politics and different ideologies. You know, the history of the American landscape was this imposition of utopian belief on nature and the perception of nature is always deformed by ideology. I started thinking about nature in terms of a vision of psychedelia but also in terms of the history of ideologies and this buzzing electronic scrim of politics, chemicals and pollution. Nature isn’t pure and I wanted to access something that was real as opposed to something that was idealized. I want to get to where nature is in my head. On one hand, it can contain a visionary experience but it’s also this social political construct that is sick and cranky.

Rail: This really reminds me of Frank Moore, whose landscape paintings of Niagara Falls and Yosemite National Park addressed those same issues. Did you know Frank’s paintings?

Tomaselli: Oh yes, we were friends and had a lot in common.

Rail: Wonderful! You know we were old friends, we went to college together— he was a lovely man. Frank really investigated the science and politics of that whole natural world construct…

Tomaselli: Frank and I talked a lot about that stuff. He was a special artist and I miss him dearly. We spoke a lot about the dichotomy of nature and culture and how they deformed one another and how this deforming was the closest to nature you could get. But we loved it, even though we knew it was a mutant. Part of the way me and Frank reconciled our love of the mutant is through gardening— the cultural shaping of nature. You get to be a God, weeding out the things you don’t want and accentuating the things you want to see or eat.

The ideal of gardening has positive connotations but the idea behind bioengineering has bad ones. That dichotomy between where it was good and where it was bad was the place we both found interesting.

Rail: We’ve talked about Frank Moore, Alex Grey, James Siena. Are there other artists that you feel particularly close to among your contemporaries?

Tomaselli: I think Amy Sillman is a really brave painter who takes all kinds of risks and I’ve learned a lot from watching her pay attention to her intuition. Her work is funny, sad and beautiful. I think Philip Taaffe is an artist who has been making good art for a long time. He’s never been afraid to access the multiplicity of patterns in nature and ancient cultures. I admire these artists for their audacity in trying to access a tough minded and intelligent beauty in a cynical world.

Rail: Now that you’ve become well known for making paintings, do you ever think about doing installations again? The giant painting you showed at the Whitney Museum in 1999 seemed so vast and the scale was so overwhelming, that it brought to mind the idea of an installation. It felt like a kind of surround experience.

Tomaselli: That’s funny, because I was initially approached by Eugenie Tsai of the Whitney to do a site specific installation. She asked that same question of me because she had seen my early installations at PS1, Artists Space and White Columns. I said I’d think about it and then had this idea to do a walk in painting that would contain the world alluded to in the picture. The more I started planning this, the more I started thinking that it was a gimmick. I felt that attempting to make a convincing, intense painting and trying to overwhelm the viewer through scale— that this was a challenge in and of itself. So I went back to Eugenie and said I want to do this big giant painting but without an installation element. She said go ahead, and she was really nice about it, but it did get me to thinking about how I pretty much have left installation behind. I now have this ongoing dialogue with making flat visual art. I’ve limited myself to two dimensions, but within that I can do anything I want. To be honest, installation seems quite limited in comparison. My last installation is still on view at the hall of science in Flushing Meadows, Queens. It's an architectural, site specific public art project called "10 Kilometer Radius." I felt like that was a good way to end it.

Rail: So you are a painter.

Tomaselli: I guess I became a painter. Fortunately or unfortunately, that’s what I am now.